Detroit wasn’t just a city: it was an idea of America. It was the place where technology married utopia, where every single engine produced seemed to move not just four wheels, but an entire social system. When deindustrialization hit and the social system faltered, Detroit did not stop being a symbol. It just changed the kind of symbol it represented: from capital of industry to epicentre of urban collapse, from manifesto of emancipation to portrait of disillusionment.

In the late 1980s, something new emerged in that void: a new language, a new rhythm. Techno continued to speak of bodies and machines, of cities and memories, of Blackness and future. It continued to speak of Detroit and what happens when utopias reach the end of the line.

Ignored by the American music industry, Detroit techno gained recognition abroad. In post-reunification Berlin, it found an unexpected audience and a second home. The music evolved, but its Black, working-class origins stayed at its core.

1. The Birth of Techno in Post-Industrial Detroit

by Cesare Alemanni

Detroit has long been the capital of the American industrial dream. Between the 1930s and the 1970s, in Detroit more than anywhere else the fordist synthesis of production and progress became flesh and metal: millions of cars from Ford, GM and Chrysler (the so-called “Big Three”) were mass-cranked out, whole neighbourhoods sprang up around the factories and the working class managed to get a foothold in the middle class. In its heyday, Detroit wasn’t just a city: it was an idea of America (and, osmotically, of the West). It was the place where technology married utopia, where every single engine produced seemed to move not just four wheels, but an entire social system.

Working on the assembly lines of the “Big Three” meant being able to afford a house, send the children to school, and climb a few rungs on the social ladder. For more than fifty years, thousands of African-American families arrived on the shores of Michigan from Southern cities, lured by the prospects of emancipation promised by the pact between capital and labour which underpinned the social and organisational dynamics of mass production.

This pact, however, proved fragile. The 1973 oil crisis, runaway inflation, increasing automation and globalisation marked the beginning of a downward spiral that turned Detroit into a symbol of the decline of American industrial power.

The African-American community paid the highest price. As factories shut down, tens of thousands of jobs disappeared within a few years. Whole neighbourhoods, once vibrant, sank into silence. The tract houses that workers had bought on installments fell into disrepair. Schools emptied.

And, as the de-industrialisation carved a material void, federal policies helped to worsen the social one. During the 1980s, Kennedy and Johnson’s war on poverty gave way to Reagan’s “war on drugs”, which turned out to be largely a war on Black people. Detroit’s African-American neighbourhoods were increasingly conceived as areas to be contained, disciplined, and punished. Once an engine of integration, the city became a laboratory for economical, social and cultural segregation.

Detroit did not stop being a symbol. It just changed the kind of symbol it represented: from capital of industry to epicentre of urban collapse, from manifesto of emancipation to portrait of disillusionment. But in this - social, economical, existential - void, a new language, a new rhythm began to sprout in the late 1980s. No longer the clatter of presses, but a synthetic, alien pulse.

At a superficial glance, techno may appear to be simple, geometric, almost bare music. A regular, square rhythm built around a rhythmic grid that repeats endlessly: the famous “four-on-the-floor”, bass drum on every beat, snare drum or hi-hat on even accents. But within this basic structure lies a world. Like an assembly line that can adapt to new cars without changing the principle that drives it, techno is also infinitely adjustable. And it is precisely this ability to compose and decompose, to replicate and vary almost endlessly, that is its deepest DNA.

Techno sound is the child of assemblage, repetition and sequentiality. In this sense, it is structurally related to factory work, not only in its aesthetics - the metallic sounds, the cold lines, the rhythmic mechanics - but in the very logic of its construction. Every techno track is a sonic assembly line, a production process that turns time into loop, noise into rhythm, monotony into trance.

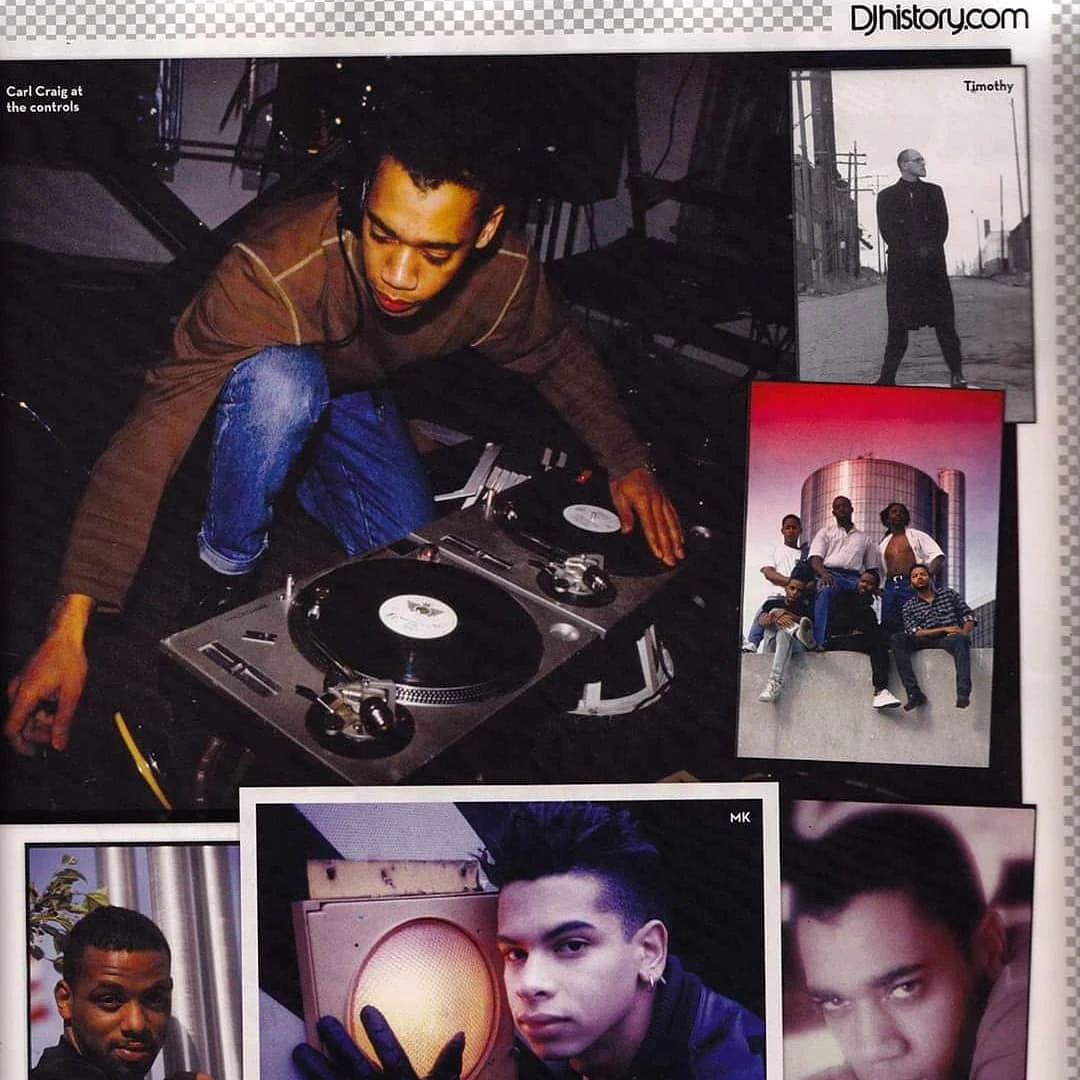

But techno was born not just out of the factory, but out of the hybridisation of seemingly irreconcilable musical worlds and imagery. Its pioneers - Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson: “The Belleville Three” - were young African Americans shaped by listening to the late-night broadcasts of The Electrifying Mojo, a visionary DJ who played Aretha Franklin and the B-52’s, David Bowie and the Funkadelic, Herbie Hancock and Kraftwerk’s icy electronica, Motown soul and the Throbbing Gristle on Detroit’s public radio frequencies, without hierarchy or barriers. In the mid-1980s, Mojo wasn’t just a DJ: he was a bridge between worlds.

Meanwhile, the proximity of Chicago provided other stimuli. Through syncopated reworking of disco hits, gay African-American DJs like Frankie Knuckles gave birth to House music, a pulsating and highly erotic sound that began to circulate in Detroit as well. The two cities talked to each other through mixtapes, late-night rides, and shared clubs. But, while house retained a certain euphoria in its vocals, techno chose silence. It eliminated lyrics. No narrative, no confession. Just sound.

Atkins, who had studied communications technology and was inspired by Alvin Toffler’s futurist theories. defined it as “cyberfunk”. May said only half-jokingly that techno was like “George Clinton and Kraftwerk stuck in an elevator”. Saunderson, on the other hand, explored a more danceable dimension, a kind of “Motown techno”, but no less radical. Together, the three of them created music that, like a machine, lived on internal combustion. Techno didn’t want to be listened to: it wanted to be felt. In clubs, in warehouses, at raves, bodies moved no longer to sounds, but to impulses.

For Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson, techno was a message from the future. Not a glossy future, but an uncertain, post-human tomorrow. Techno was an Afro-futurist gesture that broke the dominant narrative about “Black music” - linked to the expressiveness of blues rhythms and to their soul, dub and hip-hop reinterpretations - and reimagined the Black body as a dancing machine, as a cyborg.

Outside the threads of the mainstream music market, ignored by the American discographic industry, in the 1990s and 2000s Detroit’s techno found recognition where no one would expect it: in Europe. It was in post-reunification Berlin that this synthetic pulse met a natural echo. Dismantled factories, bunkers, former GDR buildings converted into clubs: everything seemed designed to accommodate this sound. Amid the historical rubble and new post-Wall utopias, the Berlin raves of the early-1990s adopted techno as the soundtrack of transition.

Yet, even as it became more complex, more layered, more global, the link between techno and its roots never quite broke. Techno’s African-American, working-class, and urban origins remained etched into its frequencies. Every beat contained a piece of history, every track was a sonic archive of collapse and reinvention. Techno continued to speak of bodies and machines, of cities and memories, of Blackness and future. It continued to speak of Detroit and what happens when utopias reach the end of the line.

2. Techno Rebels: Underground Resistance

by Michael

The Underground Resistance (UR), founded in Detroit in the early 1990s by Jeff Mills, Mike Banks, and Robert Hood, represents as a key force in the development of techno music, particularly within the context of Black cultural expression and resistance. UR’s unique unison of futuristic, mechanical sounds and politically charged messaging proffered not merely a reimagining of techno but also a critique of the systemic racial and political structures that shaped both the genre and the broader cultural landscape. Key to their identity was not only their music but their decision to hide their faces, a deliberate act that underscored their commitment to anonymity, independence, and resistance.

This essay will explore the intersection of race, politics, and identity within the work of the Underground Resistance, examining how their approach to music, their political ethos, and their masked identities shaped their significance in the 21st century.

At the heart of UR's creation was the desire to resist both the commercial exploitation of Black music and the racial erasure of Black artists in electronic music. In Detroit, a city with history of Black music and culture galore, techno emerged in the 1980s and 1990s as a hybrid of Afro-futurism, funk, and electronic experimentation. Artists like Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson, also known as the Belleville Three, helped popularise the genre, but their innovations were often overshadowed by a larger commercial industry that credited white artists for the genre’s success. In response to this erasure and appropriation, UR set out to reclaim techno as a Black art form and assert their autonomy over their music, rejecting both the mainstream commercial music industry and the racial inequalities embedded within it.

As Mike Banks explained in interviews, UR's core mission was to create an underground space free from the constraints of mainstream commercialism. The name Underground Resistance itself is an ideological and political statement, invoking a struggle against oppression. Their music, however, was not just for the sake of artistic autonomy—it was a direct challenge to the racialised dynamics of the music industry. In an interview with XLR8R, a radio station in 1994, Banks emphasised, “We’re not here to simply entertain you. We’re here to disrupt the system”[1].

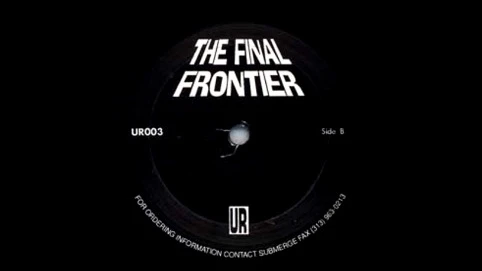

UR’s music was intentionally militant and political, speaking to issues of racial inequality, Black autonomy, and social justice. Tracks like “Riot” (1991) and “The Final Frontier” (1992) served as sonic manifestos for the group’s ethos. These tracks weren’t just about creating a new sound; they were a vehicle for articulating resistance against economic disenfranchisement and racialised oppression in Detroit and beyond. The use of mechanical, robotic sounds and aggressive rhythms symbolised the harsh realities of urban life, while also evoking a sense of empowerment and defiance against the dominant socio-political order.

One of the most prominent tracks in UR’s discography, “Revolutionary”, features the phrase, “The revolution will not be televised,” a slogan often associated with the Black Panther Party. This reference to Black radicalism firmly places UR in the tradition of political resistance movements. Through the track's grim, industrial beats, UR set the stage for techno to become a medium for political mobilisation, much in the same way that soul and jazz had been in the past.

Another example is “Land of Confusion” (by Armando in 1995), a track that directly critiques the racial and political tensions of the time, offering a metaphorical call for a new order. The juxtaposition of these hard-edged techno beats with political commentary offers a clear rejection of the status quo, insisting on both an aesthetic and a political revolution. As Jeff Mills noted in a interview, "Techno is a reflection of the conditions of the world we live in, but it is also a call for change, a cry for something better”[2].

The political edge in their music not only reflects the personal struggles of the group but also engages with broader issues in Black political thought. The mixing of Afro-futurism, a philosophy rooted in speculative Black identity, with techno, allowed UR to reframe the genre as one of Black empowerment. Afro-futurism imagines a future in which Black people have control over their cultural narratives and technological landscapes, and UR’s music and visuals offered a sonic manifestation of this vision. The cybernetic, futuristic sounds of their tracks suggested that technology, far from being an oppressive force, could become a means of empowerment and transcendence for marginalised communities.

One of the most striking and unusual aspects of The Underground Resistance’s identity was their choice to hide their faces, a decision that carried deep political and cultural significance. While many artists in the electronic music scene use visual identity as a way to market themselves, UR deliberately rejected the cult of personality and celebrity that dominates the entertainment industry. The group’s decision to hide their faces—both in public appearances and in photographs—was a statement of their belief that the message and the music should come first, rather than any individual persona.

This anonymity is often seen as a resistance to the forces of commodification and individualism that characterise mainstream popular culture. By masking their identities, UR members sought to focus attention on their collective message and artistic expression rather than their individual personas. In an interview with The Wire in 1997, Robert Hood explained that the decision to wear masks was a rejection of the system that seeks to individualise artists and profit off their image: "We wanted to remain faceless because this movement is about the music and the people, not about the individual”[3].

Furthermore, the decision to hide their faces can be understood within the context of Black invisibility in mainstream culture. In a society where Black identity is often commodified or stereotyped, UR’s masked faces were a form of self-determined invisibility. The masks, therefore, could be interpreted as a tool for empowerment, allowing UR to control their narrative outside the confines of the industry’s expectations. As Mike Banks noted, “We represent something bigger than ourselves. The face is not important. What’s important is the message”[4].

By rejecting the emphasis on personal identity, UR aligned themselves with the ideals of radical anonymity that were championed by earlier Black radical movements, such as the Black Panthers and the Nation of Islam, where the collective identity often superseded that of the individual.

The influence of UR’s political and racial messages has persisted into the 21st century, even as techno music has become more mainstream. Today, the racialised dynamics of the electronic music industry are still evident, with many Black artists still marginalised or erased from the history of the genre. As electronic music continues to gain global popularity, UR’s commitment to self-determination, Black autonomy, and resistance remains vital, as these principles offer a corrective to the appropriation and commodification of Black culture in electronic music.

UR’s decision to hide their faces and their rejection of individual fame resonate with current trends in music and activism, where anonymity and collective action are seen as powerful forms of resistance. In a world that often prioritises celebrity over substance, UR’s decision to remain faceless reflects a commitment to the greater cause, rejecting the commodification of their art in favour of its political and cultural power.

Moreover, the group’s focus on Afro-futurism continues to inspire younger generations of Black artists who seek to forge their own path in a predominantly white industry. The concept of Black techno, an emergent genre that takes the roots of Detroit techno and reasserts its connection to Black identity, is gaining traction in both underground and mainstream circles.

The Underground Resistance’s legacy in the techno world is deeply tied to its political engagement with race, its commitment to Black empowerment, and its refusal to conform to the commodifying tendencies of the music industry. Their music, which blends futuristic sounds with politically charged messages, serves as both an artistic innovation and a radical statement against racial inequality and cultural appropriation. Moreover, their decision to hide their faces underscores their belief in the collective, rather than individual, power of Black creativity. In the 21st century, their influence endures as a touchstone for Black resistance in music, demonstrating that the politics of race, identity, and anonymity continue to shape the genre in profound ways. The Underground Resistance has shown that music can be not just entertainment, but a weapon for cultural, political, and social change—a legacy that continues to inspire today’s Black techno artists.

Notes:

[1] Mike Banks on XLR8R, “THE UNDERGROUND RESISTANCE”, 1994.

[2] Jeff Mills on THE TALKS, https://the-talks.com/interview/jeff-mills/, 2016.

[3] Robert Hood on THE WIRE, The Underground Resistance and Identity, 1997.

[4] Mike Banks, https://www.redbullmusicacademy.com/lectures/mad-mike-banks-tresor-berlin-detroit-lecture, 2018.

3. Turntables, Repetition and Intuition: a word with Tyler Blint-Welsh and Ryan C.Clark

by S. Himasha Weerappulige

In a culture and music industry that devours, swallows and spews back sounds, often emptying them of their most historical meaning, tracing back the movements of what led to the birth of a genre is a precious act.

This is particularly evident in music, where Black cultural expressions have often been commodified, de-racialized and rebranded into new gentrified spaces. That said, it would be of course counterintuitive to see culture as rigidly essentialist, being culture itself inherently dynamic and ever-changing. Black American culture itself is the result of centuries of transatlantic hybridity, as Paul Gilroy would call it, though it was also forged by centuries of colonialism, migration, oppression and resistance. While critiquing cultural absolutism however, Gilroy also acknowledges that not all cultural exchanges occur on equal footing — some forms of cultural borrowing can reinforce existing power imbalances. This is particularly visible in the history of Techno music, whose Black and working class origins are neglected.

From the the end of the seventies onwards, Detroit’s Black youth sparked a new wave of social music in the shadow of economic collapse, creating new ecosystems that created jobs and shared economy of music technologies. With Motown’s exit leaving a cultural void, they began to move towards a more cybernetic soul. In its place, an underground, more intimate scene emerged—built on turntables, repetition and intuition.

They fused soul, funk, and electronic elements into spontaneous flows of sound, crafted in real time for the dancefloor. These rhythmic and textural shifts mirrored the quick-fire reactions of minds navigating an overwhelming, high-speed world. As deForrest Brown summarised it: «The sound of tecno exists as a peak intersection in Black history, reorganising centuries of black cultural expression under capital and empire into material and usable vibrational technology». Examples of black social music such as techno, «are a direct result of black people learning to feel, speak and be heard while in bondage (...) It expresses an inherent romance and trauma that carries with it centuries worth of stories»[1] whilst also looking at the future, creating a timeless, quasi circular continuum.

Expanding on the concept of cultural hybridity named before, it could be argued that black social music distances itself from a simplistic idea of linear and forward-looking “progress”. The motion is more circular, and dissipated, and as for any circle in euclidean geometry the origin point is a mere point of convenience on the line. it’s wherever you want it to be. Yet it’s constantly connected to all the other points[2].

The words that follow are the results of an exercise of shedding light on some of these points, through the interviews to Tyler Blint Welsh, who has been composing a collection of 100 black techno djs on tintype, and writer, tonal geologist, ethnomusicologist Ryan C. Clark, who is also part of the core of the festival Dweller Forever.

Act 1: Techno Tintypes

It was a warm beginning to our conversation. I mentioned that I was currently in Rome. The rain had been light and steady all day. He shared that it had been raining where he was too. Curious, I asked about his location: Brooklyn, New York City.

Himasha: So I saw that your project started with a trip to Berlin? And what’s your own connection to techno? How did you first get into it?

Tyler: I found myself drawn to tecno, because I was drawn to the spaces where techno was the soundtrack. There was freedom there—a different kind of energy. Then I learned the history, and that deepened my interest. Now I kind of joke that going out is “research.” Sometimes I go out to meet DJs, to shoot them, to experience the music live. It’s become part of my practice. One of the first things I did in Berlin was visit a big exhibition on the history of techno, especially the connection between Detroit and Berlin. That was the first time I got exposed to techno’s Black roots. It sparked this curiosity, so I started researching—reading, watching documentaries, just diving in. At the same time, I was learning to make tintypes. And then Dweller Festival posted their lineup, and something just clicked. I had this feeling like, “Oh—maybe I could tell this story using tintype photography.” I wanted to contribute to telling a lesser-known history of techno, especially around Black DJs and artists. That’s when the project really started to form. I began shooting in February of last year.

H: What did you notice about the Berlin scene that made you feel there was a need to highlight the Black roots of techno?

T: Berlin’s relationship to techno is interesting. On one hand, there’s deep respect for techno as an art form. But I also noticed that not everyone really understood or acknowledged where it came from. Some people knew about its Black origins, but many didn’t. Me in the first place. And it made me think—if this story is still under-told even in Berlin, then there’s definitely space to amplify it globally.

H: You chose tintype photography to tell that story. I find it interesting that it gives a ghostly nostalgic look, whilst depicting something quite futuristic in it’s soul, and clearly also very current since you’re taking the pictures in this moment. There’s also something poetic about using metal—an industrial material—to document a genre like techno, which also emerged from industrial cities like Detroit.Why that medium in particular?

T: Partly, it was the process I was already working with, but also—tintype is inherently archival. It's durable, tactile, and historic. It’s made on metal, and it can last hundreds of years. So I thought: If I’m telling a story about lineage and legacy, I want to do it in a medium that reflects that permanence. I wanted to make physical artifacts—images that can exist beyond my life or the DJs’ lives. There’s this subconscious link between the medium and the music. Techno came from the factories, from that mechanical rhythm. And tintype has that same rawness, that sense of being grounded in something physical and real.

H: And what about the DJs—how did they respond to being photographed this way? How did you start connecting with the DJs, and did the shoot spark any conversation?

T: Honestly, a lot of them were into it. Some DJs don’t like being photographed at all, but the process is different—it’s intimate and collaborative. The format is raw, and the images feel honest. There’s something subversive about capturing these artists in a medium that’s so permanent, especially in a culture that can be intentionally secretive. It flips the idea that techno DJs are hidden or anonymous. The conversations were definitely more personal. I’m not so focused on the club scene or the business side of it. I’m asking people about their first experiences with techno, what the music means to them, and what the community looks like. Of course, the industry comes up—everyone’s had their struggles—but it’s more about identity, memory, emotion.

H: How did they feel about the way techno’s history has been framed—especially the whitewashed narratives?

T: It varies by generation. Older DJs definitely went through periods of frustration. They saw something they built get taken from them and repackaged. Many of them live hard lives. But a lot of them are also at peace now. They’ve stuck with it, they’re still touring, still relevant. Some of them have had to let go of the anger because you can't carry that forever.

H: That’s such a big theme—how communities reappropriate and protect the things they’ve created. The joy gets taken out of it.

T: Exactly. Music should be a space of joy, and I think a lot of these artists have found ways to preserve that. They know the history, and they’re still here making art. That says something powerful.

Act 2: “Tecno is the music you’d get if you counted forever”

Himasha: Hi Ryan, tell me more about you?

Ryan: I am a lab manager for a marine science department. I was a geologist for about 10 years, mainly I analyze, describing various samples. We go out to the Gulf of Mexico, which I'm still going to keep calling the Gulf of Mexico, and we do some coring. We basically core the bottom of the sea surface, pull it back up and then do some chronology, date it, try to understand its biochemical signature so we can get a better sense of what was going on about 12,000 years ago.

H: That's crazy. I love how we're about to talk about music now. Well, then I'll start from the first question. How did music get into your life?

R: I'll answer that, but I'm also interested in this magazine and publication that y'all are running. And I'd love to hear more about that. It looks interesting and very useful work. But to answer your question, beginnings: I would say predominantly deals with coming from a Southern Baptist background, I was raised predominantly in the church. I was in the choir, and I think looking at the congregation and watching how music injected this moment of transcendence and togetherness. Almost where everyone morphed into this one spiritual being. Also, my mother loved music in the house. She played a lot of funk, a lot of R&B. She was into Parliament, the Doobie Brothers. She kept her vinyl collection in the closet, but didn't have a record player. I found myself staring at all of these objects and being so interested in them, but not being able to hear them. So I think there was a lot of dreaming, a lot of yearning music, but it felt a way that we lived, not necessarily something that you do or dedicate your life to, but it was always around. I went to go be a scientist and go into geology, but music was always around me. And after a while, mainly around the COVID lockdowns, I began to focus more of my attention on where my desire was, which was around music. And Dweller definitely played a role in that, but in growing up, it was very much the church. in my mother's musical atmosphere at the house.

H: That's beautiful. What led you into the sciences?

R: We definitely were working class. We stayed with my grandmother for a long time. And the idea of success was definitely bound to financial capacity. And also being from Louisiana. The American South, specifically southern Louisiana. There's so much environmental crisis going on. going into geology felt very true to me. How can I use my time to help this place I'm from, that I love? Now I try to say I'm doing that now, but in a cultural or maybe even folkloric way. The impulse is the same. How do we take care of each other? How do we come together? How do we form resilience and togetherness? It's moved into music. It used to be the dirt, but now it's the sand.

H: There's definitely an underlying theme that I could reconnect to your activity in the festival scene: the environment. How we relate to it, how we connect to people and things around us and create healthy ecosystems, right? By the way, I also am a person that studied a subject and ended up working on something completely different. But I do think that the methods and the methodologies I learned through the process are still very useful in everything else that I did after.

R: I’m resonating with you because I do appreciate and recognize the struggle it takes to lean towards your dreams to materialize a reality, not for yourself, but for the world that you wish for. It's not for the weak. So I want to give you respect for that. But yeah, in terms of bringing that idea or that methodology, that framework into a new field, I think it , I've been calling geology my art school. The projects become inherently multimodal or interdisciplinary, which to me breaks down this very colonial structure dynamic of this is what you do. And I think if your methodology is bringing different frames of thought together, in my opinion, it has a better chance of bringing more people together, because it almost speaks in different languages.

H: yeah, agreed. And it also stresses how cultures and generally art in general, works by intuition, or suggestions, right? Hence sometimes, things cannot be decoded by just one language of understanding. Music, for once, is a great example of that. building on that, I would like to know more your perspective of how black electronic music developed in the US?

R: Yeah, there's this amazing figure from a jazz pianist in the 19th century. He basically draws a tree and the tree is called the history of jazz and at its roots there's gospel. Above gospel there's blues, but below gospel there's sorrow and suffering. That's not to essentialize Black music as something that only comes from suffering, but I think you cannot underestimate the intergenerational gravity of the transatlantic slave trade and the atomizing effect of the slave trade. People, tribes, communities are all broken up and they're placed onto this land that they had no agency. They can't do it alone, but they can't even necessarily talk to each other. This then develops into field songs in the plantation, ring shouts… which are basically the spiritual method of congregating, where you move in a wise circle while giving praise tonally because different languages are being spoken. The way that Black people in America recognized how to speak with each other is through song and dance. And as that gets developed in advance, the language also begins to try to translate that sorrow, that suffering.

I think at its core, Black music is trying to figure out ways of coming together when we've been refused to do so. Basically, it's all social music. And then reassembling a sense of self through whatever materials are around you. It’s hustler dynamics too. And I think black electronic music is a generational reflection of basically pawn shop equipment that no one wanted. These rolling drum machines at the time were cheap. Now, obviously, they're prized items. Back in the day, this was gear that had been thrown away by studios that moved from Detroit to go to LA or from Memphis, Tennessee to go to New York. But mostly, it's a way to, to come together. To speak for yourself, to speak for your people, to express a degree of self-determination and self-possession in a world that at every instance has tried to strip humanity, empathy, ability. and autonomy away from you. So it's almost an inherently political gesture to speak for yourself. And I think jazz, like tecno, and blues, or gospel, all of that is, what does it mean to speak for myself? What does it mean to be for myself with the people that I care about? So it's a radical gesture at its core.

H: Yeah, definitely. Community is central to black social music practices, you see that from how it is based on a sharing economy of music technology right? Also, I've read that a lot of DJ sets in the 90's that went on air on black radios in Baltimore were directly streaming from the club! That’s insane.. the surreal poetics of the club. Which also means that you're streaming and amplifying what people are hearing in a communitarian physical space. It’s basically oral history and it echoes what you said about oppressed communities trying to find their own languages.

R: They also did that in Detroit at this bar called “Motor in the Mid”. Recordings are still on YouTube. But yeah, the radio was sending out a signal, connected to the club. And I think that's beautiful. And in that way, they're in the future. I also think about the wizard Jeff Mills playing three turntables on the radio, in the mid 80s. And when you listen back to those.. It almost feels, how to explain this. It's my first time saying this out loud, so excuse me..It almost feels like he was creating TikTok, but an audio version. He is moving so quickly through snippets of songs, through records. He's using three different turntables. This is 1987, right? it feels this fast stimulus it almost felt he was creating a feed but in radio you're listening to someone scrolling through their feed[3].

H: And next question then. What brought Dweller Forever into being?

R: Yeah, so that is more of a question for the person that created it, Frankie Hutchinson. Together with Enyonam Amexo we are the three main people that run the festival, but we don’t do it alone. Mhh.. how did i come across them? There was this video that they were streaming from the lower east side. It was called “Who does techno belong to?” and I had been interested in the black roots of electronic dance music for quite some time. And when I saw that I was like: “oh my gosh, someone is explaining it out loud!”. And again, I'm in Louisiana. This was happening in New York. I didn't know anyone there, but I knew I wanted to be a part of it. So I took a plane up to the second. During lockdown we started a blog. And from there, I think we started to consider Dweller as a larger project than how it was previously envisioned. So we've been working on it ever since. But in general, she made the call.

H: I saw you guys have educational programs too!

R: I think we wanted to be more explicit about the values that we were interested in expressing and we saw how historically skewed or maybe miscommunicated the ethics and the values of Black dance music had gotten. This music gets made in Detroit and other places, it goes to Europe and it arrives back to the Americas with a white face. We saw ourselves in a position to basically provide a counter-narrative and ultimately a counter-phenomenon to that idea. Can this music not return, but can it circulate within the community that developed it? And we wanted to do that. But we recognized that the music couldn't do it alone. So we started panels and, the blog, interviews, ways to... bring more explicit context to a music whose cultural significance had been erased or at least muddied.

H: Okay and how has it been so far? I'm sure that there's a lot of challenges, especially when the festival starts becoming an actual festival and as I said in the email, passing from an informal context and economy to a more formal economy, how do you survive that?

R: Oh, lots of talking, a lot of… not exorcism, but a lot of dealing with it together and being honest about not capitulating to the idea of infinite scale. I think being in a capitalistic society, especially if you're getting some feedback of success, the idea is to make the next thing bigger and bigger is better. And there always be a bigger, better moment in this infinite growth framework. And we said early on that we need to not behave in that way. Because again, it would go against a lot of the historical roots that we come from. I'm thinking about... Undergone Resistance and Submerge they behave at a capacity that makes sense at a human scale and not an industrial one. So we're not working through a restrictive engagement with the world. It helps. It doesn't help our, it doesn't help our wallets, but there's a larger thing going on, and this is not about making money.

H: And how do you centre the needs of the community you are talking to?

R: Yeah I mean the good thing about it is the community that Dweller emerged from a long history, even before it was even a thing. Frankie before Dweller, she co-founded Disc Woman, which is a femme-based booking agency. She was also one of the bookers for Boston, a civic club. The dance community in New York, we were already in conversation with them. We were in a relationship with all these people so we never felt alienated from what we're coming from. The people that come to dweller at least, we're in conversation with them anyway, we're friends we're coworkers. We're definitely happy to be a part of a larger ecosystem where people want to talk to us, they can talk to us. We're very grateful to be a part of a community that is not afraid to speak. To their concerns or their comments, positive or negative. So I think that's what happens. We used to set up a town hall to bring up a microphone and do all of that. But then we thought it was too formal, it almost feels colonial. So I wanted people to come find us. We're here. And I'm ranting now, but the last thing I'll say is that I don't want Dweller to be seen as this sacred object that nobody can talk down on. I think only through honesty, clarity and transparency can this thing continue to behave in relation to the world around it. I don't want it to be this thing on top of a hill. I want it to be with the people. That's where we are. And I'm happy.

H: Amazing and when's your next festival?

R: 2026, it should be happening right now, but we took a break, a sabbatical.

H: fair enough.

R: For reasons we were talking earlier. The struggles, yes. People's feelings. We're trying to work on grants, we're trying to work on fundraising opportunities, we're trying to make this thing work so we can survive and not get burnt out. Because however extravagant it looks it is a DIY project it also takes time to find the right partners to do it with absolutely and it goes back to what we were saying about the model of capital. We wanted to trust ourselves that we could take a pause and that the people that would be there for us would still be there for us so it was a decision that was tough to make but we had to because we couldn't do it any other way.

H: I'd love to end the interview with recommendations: music, tracks, readings?

R: I spoke to Jeff Mills earlier about his TikTok DJing in the 80s, but he has a film called The Exhibitionist, which is him DJing on three turntables. And that is quite profound. I've been trying to think about “How do we consider a DJ mixing cinematic”? And I think he was dealing with that question in the 2000s in a cool way. There's this amazing fundraiser for one of the OGs, the pioneers of techno music. His name's Anthony Shake Shakir. And he has multiple sclerosis, if I'm not mistaken. There's a fundraiser for him right now[4]. His music is amazing. He has this compilation called Frictionalism 1990- 2009 [5]. And it's 36 tracks of the most mind-warping music. And one song in particular that I love is called Electron Rider and My Little Black Robot. The book that I would share would be, it's a classic at this point, at least it should be, Assembling the Black Counterculture. It's very much social, material, almost a Marxist history and analysis of Detroit techno from its beginnings to now. It helps to not to essentialize blackness, and also, not to romanticize it. There’s a lot of pain, there’s a lot of sorrow, there’s a lot violence and manipulation.

H: That resonates. There’s a lot of pain in systematically oppressed and fragmented communities, mainly because the focus is survival. It was a pleasure talking to you Ryan.

Notes:

[1] https://primaryinformation.org/product/assembling-a-black-counter-culture/

[2] Ryan C Clark, “Techno as a pedagogy of suggestion”: https://www.youtube.com/live/dS7uG351xhk

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g5Jd31qDSjo

4. From Detroit to Berlin: the Atlantic Journey of Techno

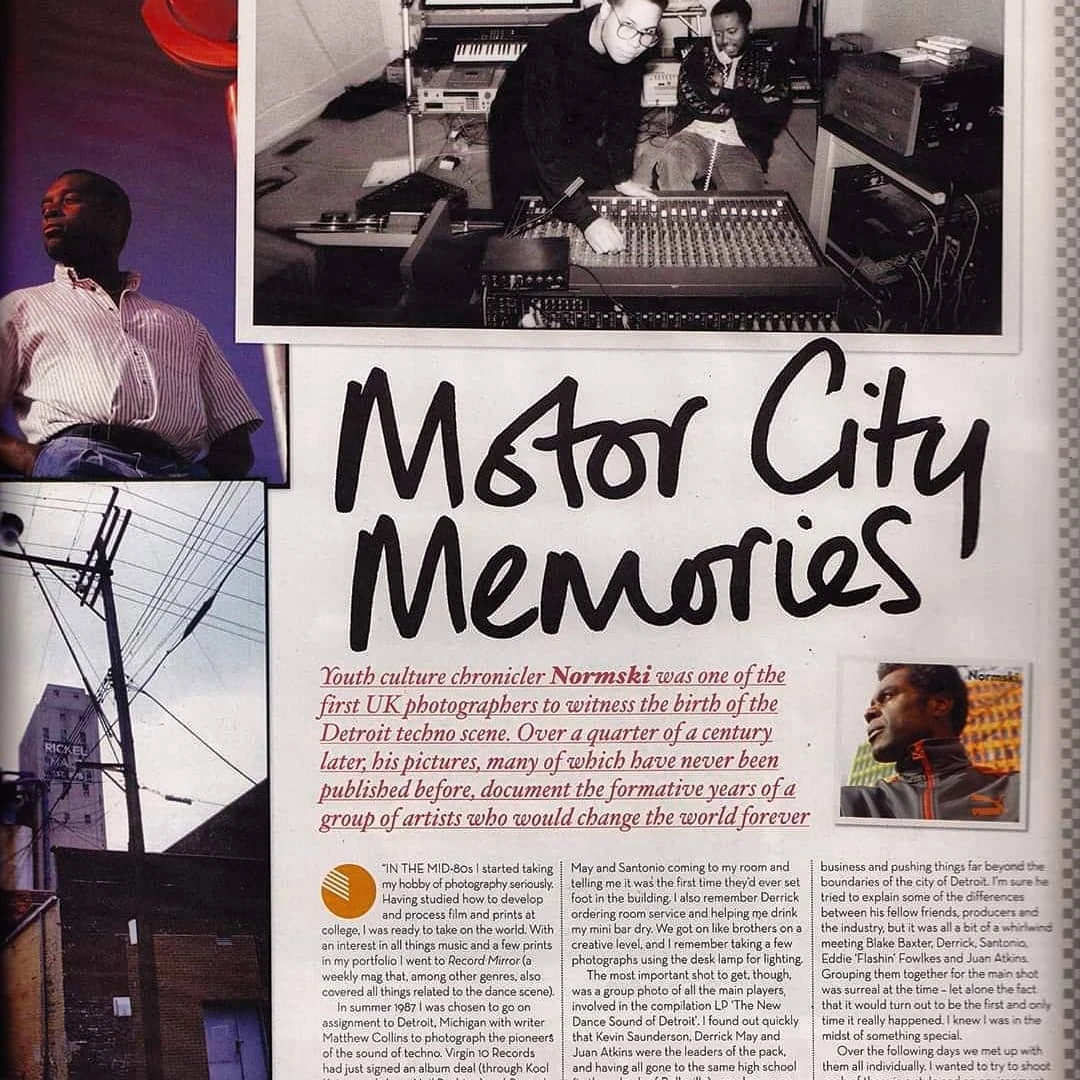

Berlin is the adopted capital of techno music, but how did a genre born overseas find its epicenter in the heart of Europe? Through interviews with Andrea Benedetti, DJ and producer, and Christian Zingales, journalist, we traced the connections that made techno travel between the two sides of the Atlantic.

di Federico Sardo

In the Spanish series The New Years, there’s an episode where the protagonists travel from Madrid to Berlin for a few days, with the specific goal of going clubbing at a venue modeled after Berghain. It’s a realistic script choice, one that many people in their twenties to forties can easily relate to. After all, for many years now, the German capital has been regarded as the world capital of techno—the city most closely associated with the genre. So much so that many fans may not even know that techno actually originated in the United States, in Detroit, under very specific and in many ways unrepeatable circumstances.

The first major issue, however, is that techno’s birth in its homeland didn’t garner much attention. In fact, aside from a few niche circles, it went largely unnoticed. The U.S. is a very business-driven country, and anything that doesn’t achieve commercial success tends to struggle to survive. Techno was strange, new, hard to understand, and had uncertain commercial appeal—hardly something the major record labels were willing to invest in. It’s true that some independent labels that would later become legendary emerged during those years, but their roots were in punk, post-punk, and the budding indie rock scene. Their main outlet were college radios, which—reflecting the country’s university demographics—were predominantly white. And even these stations had a hard time connecting with this new, unfamiliar sound: Black, dance-oriented, and seemingly non-politicized.

Andrea Benedetti [1], one of the Italian pioneers of the electro and techno scene, tells us: “Detroit is a one-of-a-kind. In the U.S., there’s white radio and Black radio, very segmented. It’s no coincidence that Charles Johnson (aka The Electrifying Mojo) shaped the minds of so many young people right there in Detroit throughout the 1980s. An African American born in Arkansas, he worked as a broadcaster in the army during the Vietnam War, where, according to his own accounts, he felt the need to play music for everyone: whites, Blacks, Puerto Ricans. When he returned from the war, he couldn’t find work in the major radio stations and ended up in Detroit, a city already in decline from which Motown had left by then. There, he found a space where he could do whatever he wanted, and every night he played a little bit of everything: Prince, Kano, Peter Frampton, Kraftwerk… In Detroit, there were parties where on one floor you’d hear commercial music, on another there’d be a new wave concert, and on a third floor this indefinable thing they called ‘progressive,’ which blended wave and italo. ‘Problèmes d’amour’ by Alexander Robotnick was an absolute cult classic.”

Surprisingly, it was “old Europe” that truly fell in love with those futuristic sounds. But perhaps it’s not so surprising, especially if we remember how Derrick May—one of techno’s undisputed pioneers—famously described the genre as “George Clinton[2] and Kraftwerk stuck in an elevator.” That is: funk, deeply rooted in Black culture, but fused with a strong element of futuristic electronics, that had long had a significant legacy in the region around the Spree[3]. In fact, as early as the 1970s, krautrock [4], and particularly the so-called “Berlin School”[5], had already given rise to a form of electronic music that was less academic, more atmospheric and psychedelic, aimed at inducing a trance-like state. A quality that would come to define both techno and, later, IDM.

According to music journalist Christian Zingales [6], the reasons for techno’s success in Europe are contextual: «The cold, hypnotic side of techno found a more receptive audience in Europe thanks to the continent’s higher level of education and its closeness to the same European influences—from new wave to synth-pop to electronic music proper—that had inspired the handful of African Americans who created the genre in Detroit».

Benedetti echoes this: “The history of techno—and to some extent house as well—is really interesting, because for the first time it’s us Europeans who significantly influence African Americans; whereas throughout the entire 20th century, from jazz to blues to rock and roll, it had always been the other way around». He goes even further: «Electro was perhaps the first truly and purely interracial music, because it drew direct inspiration from Kraftwerk and from a huge amount of European stuff. Afrika Bambaataa himself said it: ‘Kraftwerk didn’t realize the impact they had on the African-American community.’ At Bronx block parties, he came up with the idea of playing Trans Europe Express [7] and people went crazy. African-American identity is rooted in the diaspora, and I think in some ways they saw themselves in that idea of being aliens in an alien land. And the machines, the new instruments, were like new languages to create their own identity, their identity regeneration».

These were the affinities carried in the air, in the music, in the zeitgeist—but there were also more pragmatic, commercial, and record-industry dynamics at play.

Techno made its way to Berlin via London or, more precisely, along the same route that, during the “second summer of love” in the late 1980s, connected Ibiza with British cities [8], fueled by ecstasy and house music [9]. The British began discovering these new sounds coming from across the Atlantic, strengthening that ongoing musical dialogue between both sides of the ocean. Just a few years earlier, in fact, the Northern Soul craze had taken off—a danceable, Black, American import as well. As Benedetti explains: “England was the country that, from ’82 to ’85, with the global explosion of electro and hip hop, served as the first bridge. Historically, the connection between England and the United States has always been strong, even musically”.

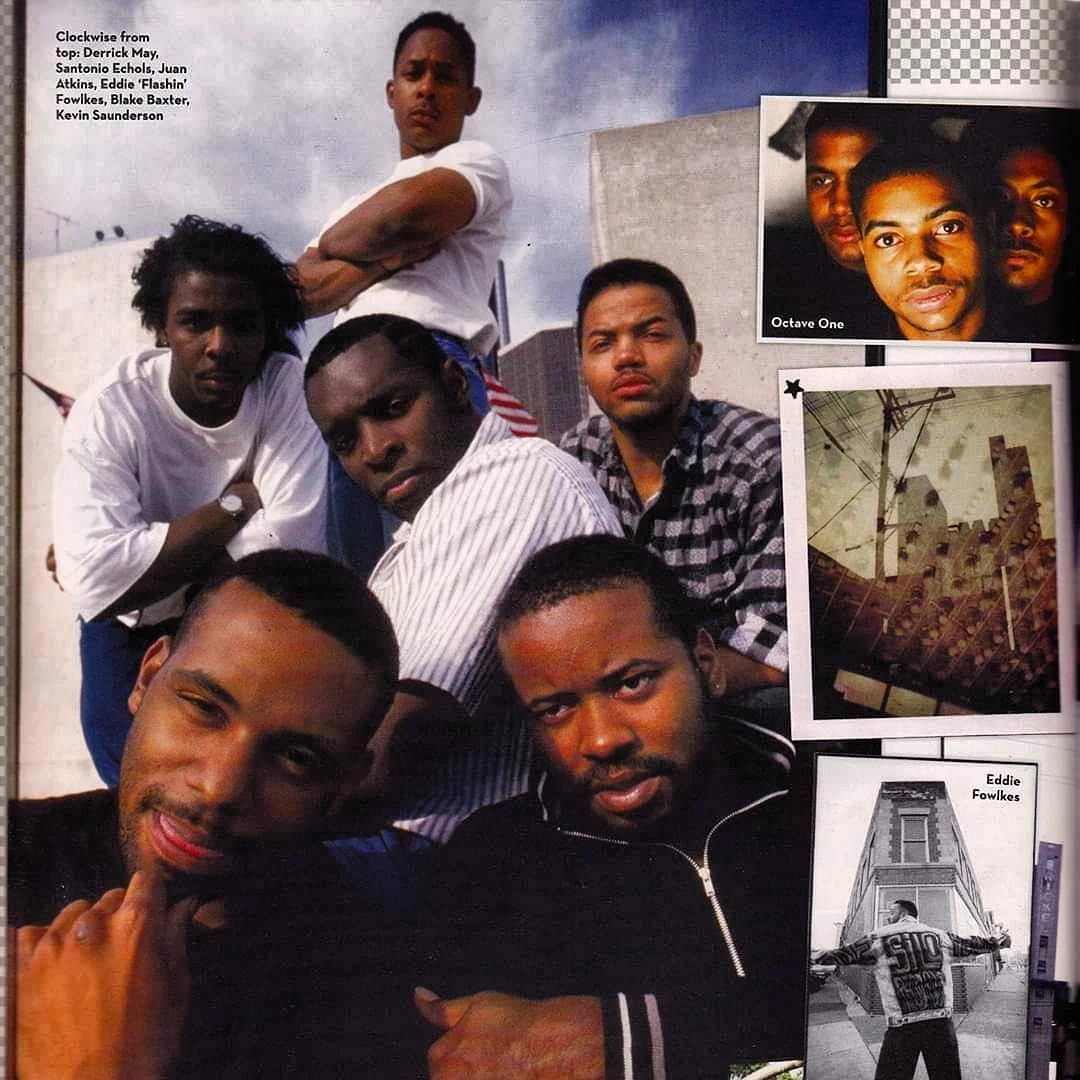

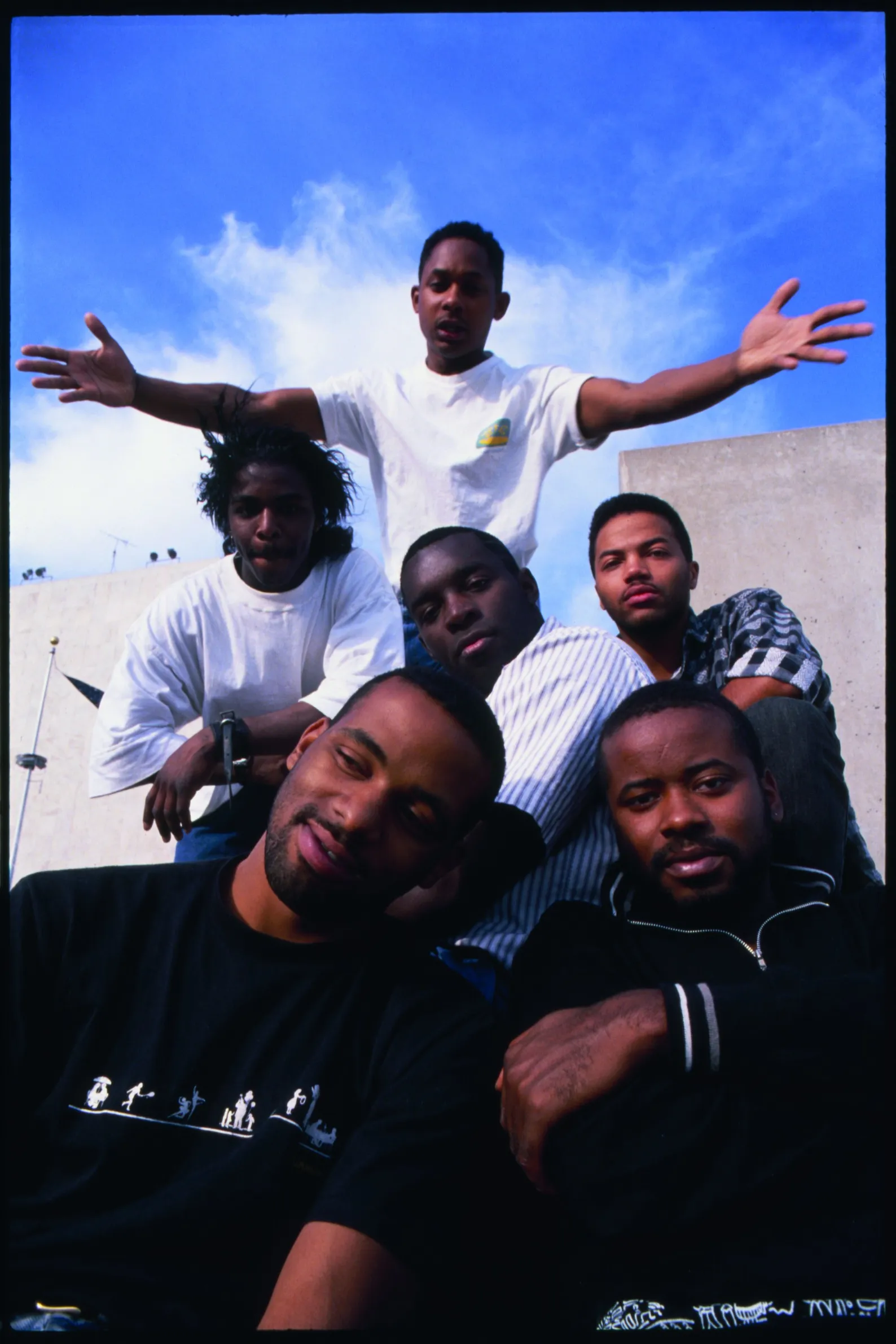

The milestone that marked the transition from one side of the ocean to the other was a compilation, which codified the genre, named it, and at the same time testified to the greater European interest compared to the American one: Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit, released in 1988 by 10 Records, a British label affiliated to Virgin. The names, among others, included Derrick May (curator, alongside Neil Rushton), Kevin Saunderson, Juan Atkins [10], Blake Baxter, Eddie Fowlkes, and many more. These pioneers began to realize that while they might not be prophets in their own land, on the “old continent” there were minds ready to embrace them.

Benedetti recounts the genesis of the compilation: “Neil Rushton was a former northern soul promoter in the UK, who opened a label called Kool Kat [11]. He happened to hear the first house music, fell in love with it, and discovered that similar stuff was being made in Detroit as well. He tried to bring them to the UK and started making licenses to distribute these records. He released them on his label, which slowly transformed and became Network, and at one point the records were selling well, so he was able to release this famous compilation that would help techno break into Europe. Before this collection, a series of compilations had been released in the Netherlands and Germany, and they had achieved commercial success: The House Sound of Chicago volumes one, two, and three; you could find the most famous house tracks. Rushton, riding the wave of these results, said to Virgin, ‘Let’s do one on Detroit,’ and eventually managed to convince them, even though they didn’t really believe in it. They told him, ‘So we’ll call it The House Sound of Detroit,’ but no way: as codified by Juan Atkins, that was called techno, exclamation point.” Zingales adds, “Material that previously had been understood as a Detroit branch of the Chicago house music was, from that point on, officially called techno, in keeping with the title of the historic compilation, officially called techno. From that moment on, in the UK, as well as in Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium, there was a proliferation of scenes that, in the very early 1990s, would shape the development of techno.”

As often happens in the world of music, historical events and their impacts, both locally and internationally, also play a role. In fact, after World War II, Germany was divided into two major nations (East and West Germany), and similarly, Berlin was split, with a profound impact on the organization and architectural distribution of urban space. On 9 November 1989, following a series of complicated economic and political crises within the Soviet model, the Berlin Wall came down. The event was monumental, and the two Germanys were reunited. Among the consequences was the sudden availability of large, inexpensive spaces in the east side of the city, left behind by Soviet architecture. It was the perfect recipe for the arrival of young and creative forces; collectives, social-art spaces, and places to dance began to emerge, all within post-industrial settings. Something similar had already been seen with New York punk, and this story too would later be ravaged by gentrification, but for the time being, it provided the ideal context for the explosion of new art forms. Techno music was not just its soundtrack, but one of its main protagonists.

In March 1991, Tresor [12] opened in Mitte near Potsdamer Platz, in the center of East Berlin. Its role in spreading Detroit music is crucial, both as a club and because, within months of its opening, it also became a record label. Benedetti recounts, "The connection with Germany happened in 1987-88: Dimitri Hegemann had this label, Interfisch, which was printing cold wave in Europe. At one point, he went on a trip to Chicago, where at the record store Wax Tracks, an industrial label, they told him he could take whatever he wanted from a basket full of discarded demos. He found a project by Jeff Mills with Anthony Srock called The Final Cut, became obsessed with it, and decided to release it. In America, artists were treated badly by the majors due to money issues; even the three from Belleville weren’t doing well in the London record market. Some time later, Mills remembered Hegemann and sent him some tracks, and at the same time, the first British-imported raves were starting to arrive in Germany. In Germany, there was a great initiative by the government, which, in order to help the East integrate, began promoting affordable lease contracts. The Berlin crisis we see today is because many of those contracts, which had been signed for places at 20-25 years with very low prices, are slowly expiring. Hegemann, who had many friends in the East, took a place that no one cared about, and invited these Americans he had fallen in love with to play. From there, the apocalypse happened. Not satisfied, after hearing that spectacular music, he also created a label: Tresor."

According to Zingales, some of the common roots of the genre’s success in the two cities can be traced to: "A - purely teutonic - physiological inclination, for this kind of sound that has a very militaristic component, apart from the funk influence. And then certainly Germany's electronic tradition: from the cosmic couriers of the 1970s to the new-wave experiments of the 1980s, it is a nation that has always been very familiar with pre-techno sounds. If we add the antagonistic streak that expressed itself in various facets of underground culture, especially in Berlin, before the fall of the Wall, we get the total, a logical interpenetration between the German people and techno."

To confirm what has been said so far, if we look at the record labels of the most important Detroit Techno albums, we discover that they were almost all released by European labels. For example: Paradise by Inner City (Kevin Saunderson) was released by 10 Records in 1989; Derrick May's Innovator compilation was released in 1991 by the British label Network (with Neil Rushton always involved); the Classics compilation by Model 500 (Juan Atkins) was released in 1993 by Belgium's R&S; and finally, Tresor, after a few releases by Blake Baxter, Eddie Fowlkes, and the trio projects of Jeff Mills, Robert Hood, and Mike Banks, released albums such as Waveform Transmission Vol.1 by Jeff Mills (1992), Internal Empire by Robert Hood (1994), Neptune’s Lair by Drexciya (1999), and the list could go on.

Techno became the mainstay of a changing Berlin, and its success began to lure tourists. Meanwhile, the music continued to change: «The minimisation of techno is a thing that was theorised and realised by Jeff Mills and Robert Hood», Benedetti tells us. «They did it partly for conceptual reasons: it has always been an obsession for Hood, the first record to clearly use the word “minimal” is his. However, there was also a work about the essentiality of the groove which has somehow nullified its complexity. Mills recounted: “When we came to Europe, we realised that some of the music we were proposing was too complex, and then I had to somehow drain it and to find formulas to make it more digestible, to make room for the people on the dancefloor. Some music was too complex, too hectic”. Basically, it was a bit too conceptual a choice, because, at the end of the day, if you make it a bit too reasoned, you lose that element of blackness, which then came out in other ways, like in the music of Moodyman or Theo Parrish. They insisted on a more recognisable black component: if you listen to one of their tracks, you can hear soul and jazz in it. Today's techno is the child of a reduction. They wanted to make more digestible a project that instead ranged from Model 500's Kraftwerk-esque electronica to May's sci-fi tribalism, Sanderson's universal music or Eddie "Flashin" Fowlkes' techno soul. All that complexity is dead, completely gone».

Zingales is scathing about this: «Berlin is a devastating commercial machine, a dark-tinged amusement factory that has been able to sell an idea of techno, an amusement park where you have to dig very deep to trace the real meaning of this music.” He adds, “Just as jazz exhausted its creative drive in the last fusions of the 1980s and rock blew up with a shotgun blast along with Kurt Cobain's brains, so techno is dead. It has consumed its creative fury, staged its historical journey, in ten years, spanning 1985 to 1995.” In his analysis, however, there is also room for a silver lining: “The most valuable legacy is a combinatorial tendency of the most diverse inputs, today there is a metabolization of techno and house clichés but also a desire to rework them into new grooves that tell the story of the present. This leads to a positive balance. The best stuff coming out today is the stuff that transcends genres or cites them en passant while managing to always keep alive that fire that started it all. Beyond geographies, stereotypes and eventual commercialization, there is still a real passion, as if we were at the beginning of a new path».

Benedetti on this proposes a parallel between techno and the parable of the last century: “For me, techno was born precisely as a general summation of the universalism of twentieth-century music. Those in Detroit suffered greatly in America from the use of the word techno when the Prodigy and the Chemical Brothers exploded, because for the generalist media anlpything that was electronic could be called techno. But in fact for me it is now a term like rock, a mega-container: rock today can mean either Battles or Maneskin. Techno showed us the future, at the end of the twentieth century. It gave us the idea that there could be a popular relationship with the avant-garde, because so many choices in techno music are pure avant-garde, but at the same time also deeply visceral.”

For Zingales, hybridization is the key, so it is not serious if from time to time it is one sonority or another that emerges prominently: “The magic of techno is its being able to pose as a magnet that incorporates the most contrasting forces between them, a sonic body of constant hybridization between ‘black’ and ‘white,’ funk and electronica. I don't think there is a problematic issue when one of the elements in play prevails: historically it has happened that in some productions or strands of the genre one nuance comes to dominate rather than another, this provided that the music has its own urgency.”

The soul of techno lies in the very idea of innovation, its original lesson being to be open to the unexpected, the unheard, what has never been seen before. Benedetti reminds us that, in a lecture at the Red Bull Music Academy, Mike Banks said, “It is useless for you to come to Berlin. Berlin has been there now. You have to create a new Berlin, you have to make sure that you are always creating new things.” He concludes with a hope: “The idea of being together at the end is such a part of our being that you still see it in the kids: whatever they go dancing to, the desire to be together is still there.”

The story of the relationship between Detroit and Berlin reminds us once again how everything blends in music. To conclude, we would like to recall another Berlin history, that of Basic Channel, two very white Germans (Moritz von Oswald and Mark Ernestus), who heavily introduced another black element into techno, namely Jamaican music, generating the subgenre of dub techno, and then collaborated directly with Caribbean mc's and singer through the Rhythm & Sound project.

Perhaps it is precisely because at the turn of the century and in the midst of developing processes of globalization, techno is a music that speaks to the whole world: roots fixed in Detroit, body on a Berlin dancefloor, and head projected out into the world, if not the cosmos.

Notes:

[1] DJ and producer. In 1990 he collaborated with Lory D.'s Sound Never Seen label. He founded “Tunnel,” one of the first magazines devoted to techno, and the Plasmek label. Author of several books on the genre, including: Mondo Techno (2023) and La Visione Techno (2024), both for Agenzia X publishing house, Milan.

[2] Legendary founder of Parliament and Funkadelic.

[3] The river running through Berlin.

[4] A term disliked by its own exponents, popularized by Julian Cope's famous essay Krautrocksampler (1995).

[5] Less connected to rock than that of Dusseldorf (Kraftwerk's hometown), it has its points of reference in Tangerine Dream and Manuel Gottsching's Ash Ra Tempel (whose 1981 album E2E4 can be considered an example of proto-techno); as well as in the minimalism of Steve Reich and Terry Riley and fellow countryman Karlheinz Stockhausen.

[6] Journalist since 1998 for Blow Up Megazine. Author of several books, including the seminal Techno (2011) by Tuttle Editions.

[7] Kraftwerk song from 1977.

[8] Manchester especially stands out, so much so that it earned the nickname Madchester.

[9] Genre born in Chicago a few years before Techno.

[10] Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson, Juan Atkins aka the Belleville Three, or the artists recognized as the inventors of Detroit Techno.

[11] Homage to a Detroit soul label.

[12] Contributing to the birth of the club was Dimitri Hegemann, owner of Interfisch Records and the former Ufo Club, among others.

Donate

Donate