For more than a century, many African Americans have traveled to Paris, seeking refuge from the racism in the United States that sought to erase their identity. However, many encountered new forms of discrimination while also finding the opportunity to engage directly with the African diaspora in Europe. This has led to an extraordinary cultural relationship between the French capital and the Black America. From these encounters, artistic, intellectual, and political creations emerged, redefining the very concept of blackness. From the vibrant Paris of the 1930s—where anti-colonial political movements and jazz flourished—to the Paris of the 1980s, marked by the rise of Hip-Hop in Europe, this connection has sparked profound reflections on oppression, both in Europe and the United States.

1. The people’s Paris Noir: everyday lives, unarchived

By Hajar Ouahbi

Why revisit the history of Paris Noir through archives?

When people think of “Paris Noir,” they often picture towering cultural figures—James Baldwin’s lyrical prose capturing the city's charm, Beauford Delaney’s vibrant brushstrokes bringing its essence to life, or Miles Davis’s trumpet echoing through smoky jazz clubs. But the history of Black Paris extends far beyond its celebrated icons.

Much of this history isn’t housed in grand institutions but in private collections, family photo albums, and underground publications. Today, social media platforms act as modern-day archives, where individuals share rediscovered photographs, letters, and memories: piecing together stories that might otherwise have vanished. These digital archives shed light on the lived experiences of those who never wrote memoirs or made headlines but were vital in shaping the city’s Black identity.

By exploring materials from the 1950s to the 1990s, decades marked by postwar migrations and family reunification policies involving France’s former colonies, we uncover a history built on community and resilience. This article delves into two sources that help reclaim this hidden past: the journalistic work of Ernest Dunbar and the cinematic archiving of Johanna Makabi.

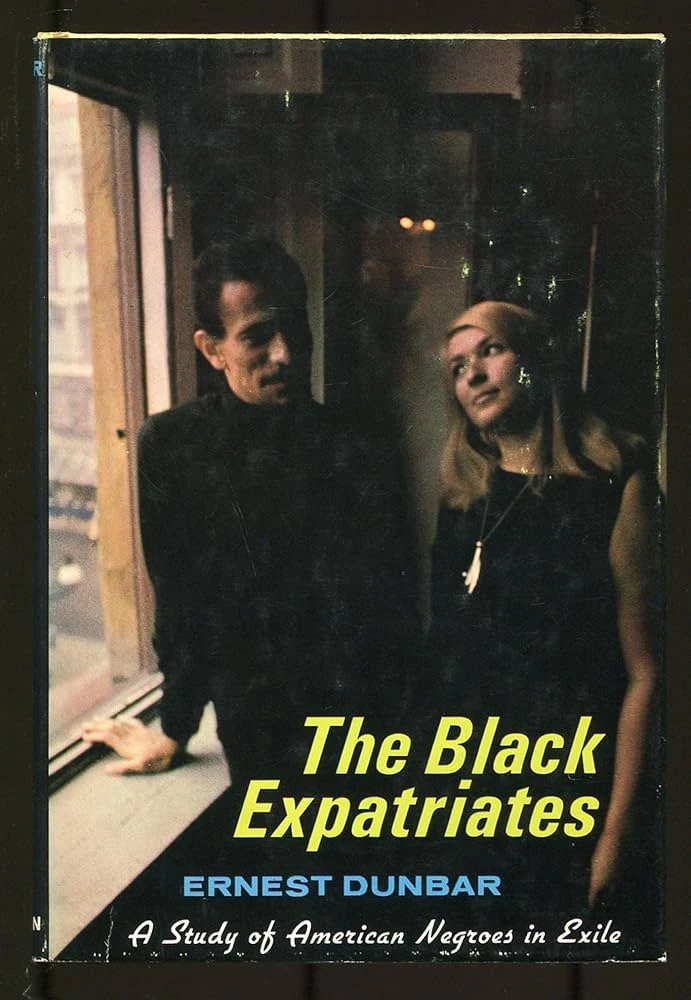

Ernest Dunbar: chronicling Black life in Paris

«There is a Paris most American visitors never see. It is not in the Michelin Guide, nor is it mentioned in tourists’ letters back home. It is the world of those expatriates, black and white, who are employing every scheme, dodge and hustle known to Western men to survive in the City of Light»[1].

In the 1960s, Ernest Dunbar, one of the first Black reporters hired by a national magazine in the U.S., documented the lives of Black expatriates in Paris. He spoke with waiters, photographers, businessmen, and students: people who, while less famous, were fundamental in weaving the social fabric of Black Paris.

Dunbar introduces a cast of characters navigating life in the City of Light. There’s Edward Barnett, an aspiring high-fashion photographer living in a cramped apartment in a working-class district. Daniel L. Johnson, a painter immersed in café discussions. Henry C. Carr, a businessman juggling ambition and racial prejudice. And Art Simmons, a jazz musician who has seen it all.

«They come here under the guise of intellectualism» Simmons remarks in the book, reflecting on the many expatriates he has encountered. «But, man, they’re phonies. It doesn’t take long to see through all that talk. You watch them, and after about a week, you ask yourself: ‘What does he do? What does he really do?’».

Paris, for all its romantic allure, was no utopia. While African Americans found relief from the overt racial violence of Jim Crow America, they encountered a different kind of racial hierarchy in France. Barnett recalls a moment in the Paris metro when the insult wasn’t directed at him but at the French woman beside him : pauvre fille (poor girl in French) a man muttered, looking at her with disdain, pitying her for being with a Black man. In another encounter, a Frenchman confided in Barnett his disdain for Algerians: «They’re not Christians! They’re different»; Barnett was struck by the familiarity of such words: he could have heard them from a Southern segregationist back home!

Dunbar’s book reminds us that the legacy of Black expatriation is shaped not only by the headline-grabbing figures but also by those who, in anonymity, found in Paris a city where they tried to carve out a space for themselves. Through his rigorous reporting, he exposes the gap between the idealized image of Paris as an inclusive, intellectual haven and the lived reality of a city divided by race and class.

Johanna Makabi: bringing family archives to light

Unlike Dunbar, who chronicled his time in Paris through reporting, filmmaker and producer Johanna Makabi reconstructed Black Paris through personal and family archives. Her work breathes life into the overlooked histories of figures like Négritude co-founder Paulette Nardal and pioneering African actress Mbissine Thérèse Diop. But it also tells the everyday stories of Black life in Paris: stories captured by her own father.

A visual heritage of exile

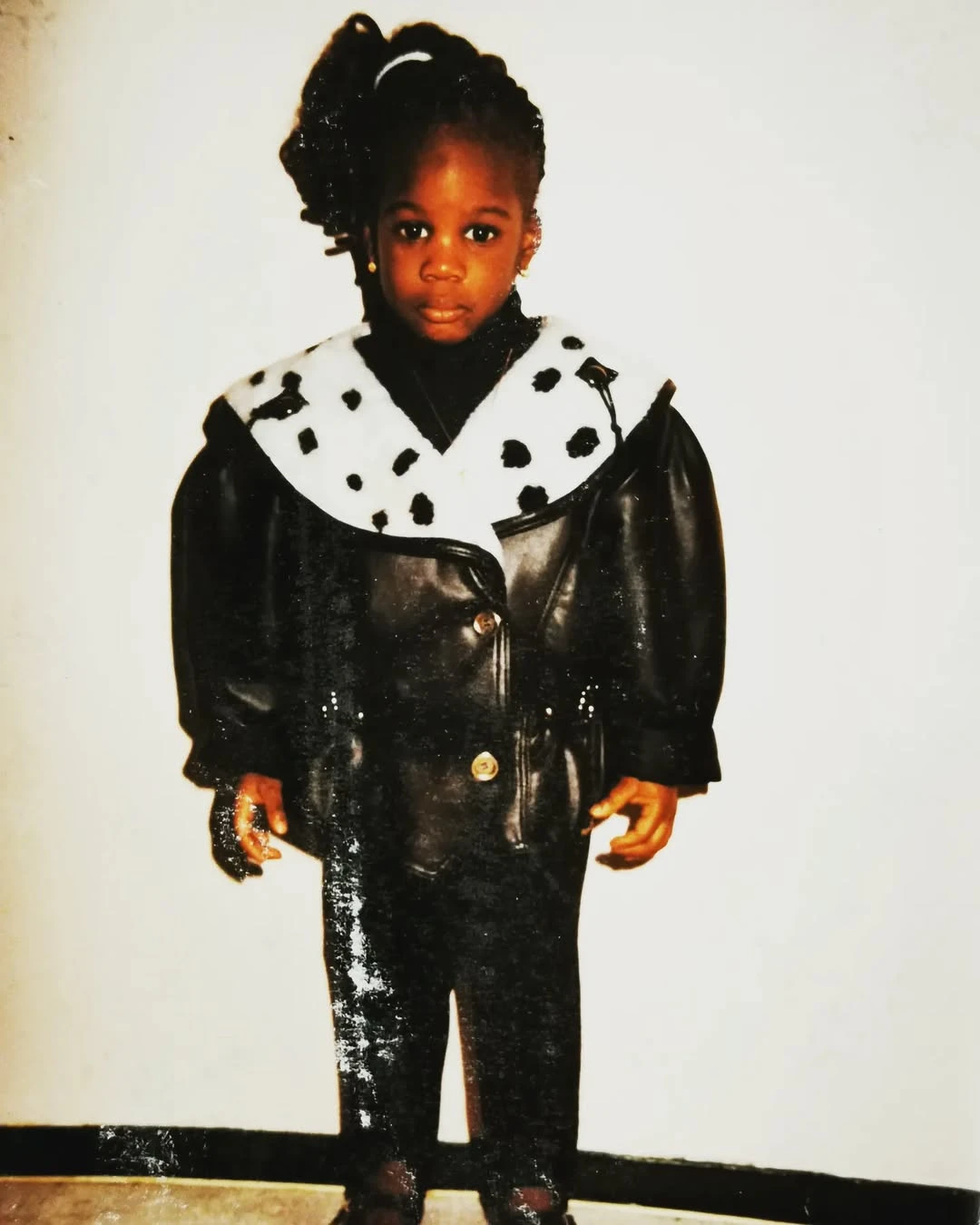

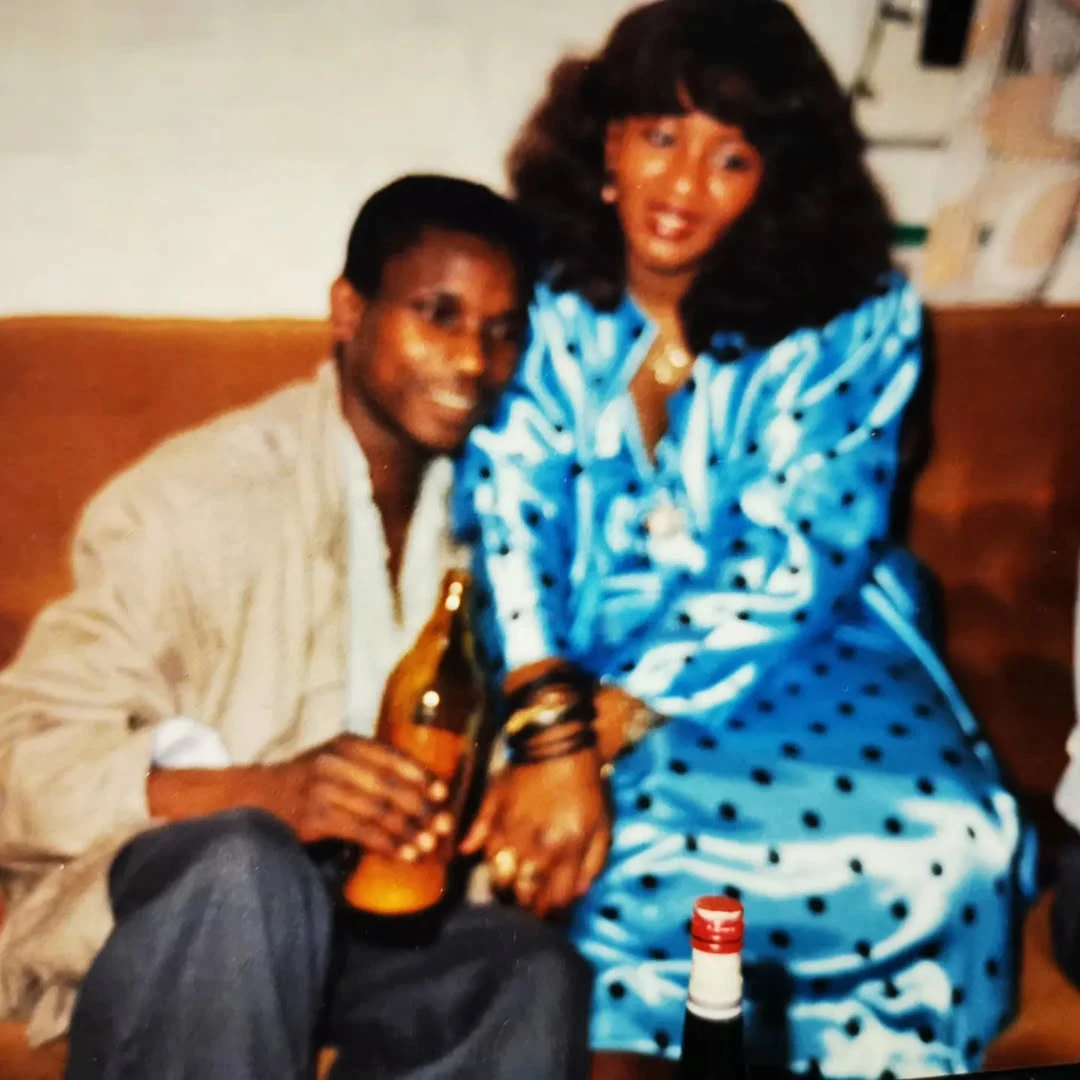

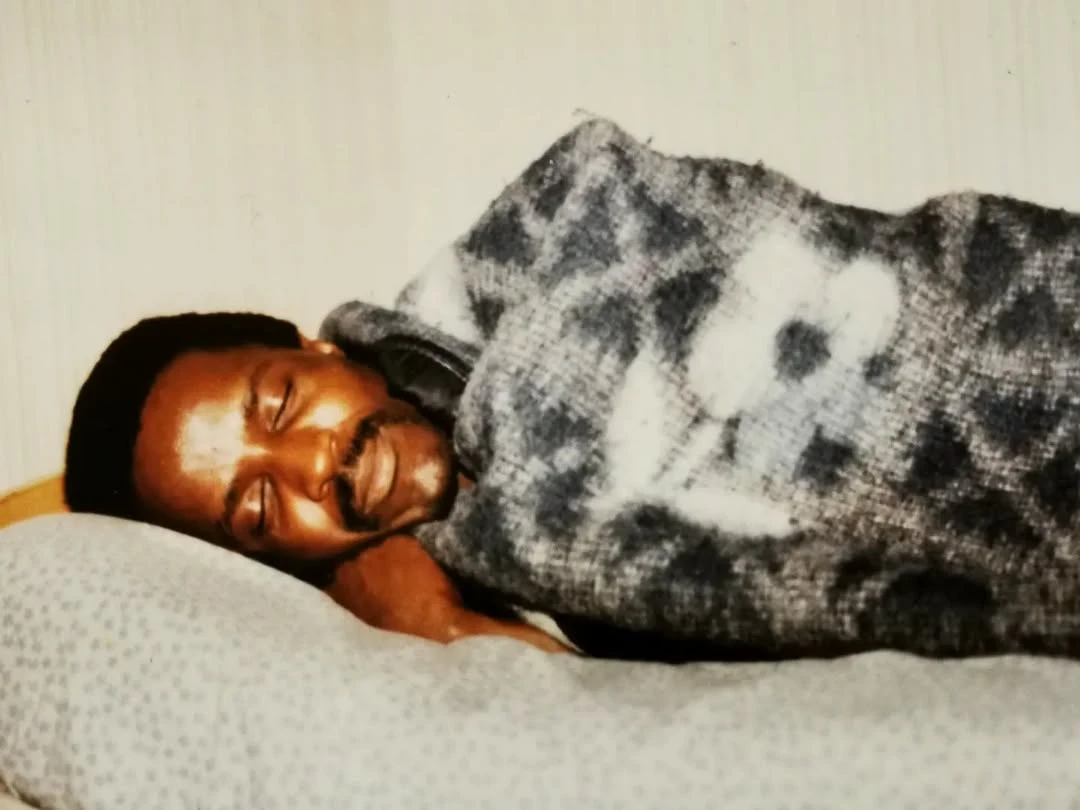

Born to Congolese parents, Johanna Makabi grew up surrounded by photographs and videos that connected her family to their homeland. «My parents, exiled far from their country, used these media to maintain a link with our family in Congo», she explains. Her father documented daily life in Paris, while relatives in Congo sent back cassette tapes: an exchange of images and voices that kept their world connected.

As a child, these images felt foreign to Makabi. «They were so different from what I saw on TV or in the media, and for a long time, I rejected them». But as an adult, she rediscovered them with a newfound nostalgia and political awareness. She saw in them a rare and valuable representation: a middle-class African family in Paris, defying the narrow stereotypes of immigrant precarity often pushed in mainstream narratives.

«There is something deeply political about reclaiming these images», Makabi notes. «For so long, the dominant narratives about Black and immigrant communities in France have been ones of marginalization and struggle. While those realities exist, they are not the only stories. Our histories are full of joy, creativity, and resistance».

Determined to bring these hidden histories to light, Makabi began sharing her father’s photographs on social media, transforming them into a form of artistic storytelling. «My father never imagined these photos could be considered art, and I wanted to honor them», she says. She deliberately includes blurred or imperfect images, preserving their raw, unfiltered authenticity.

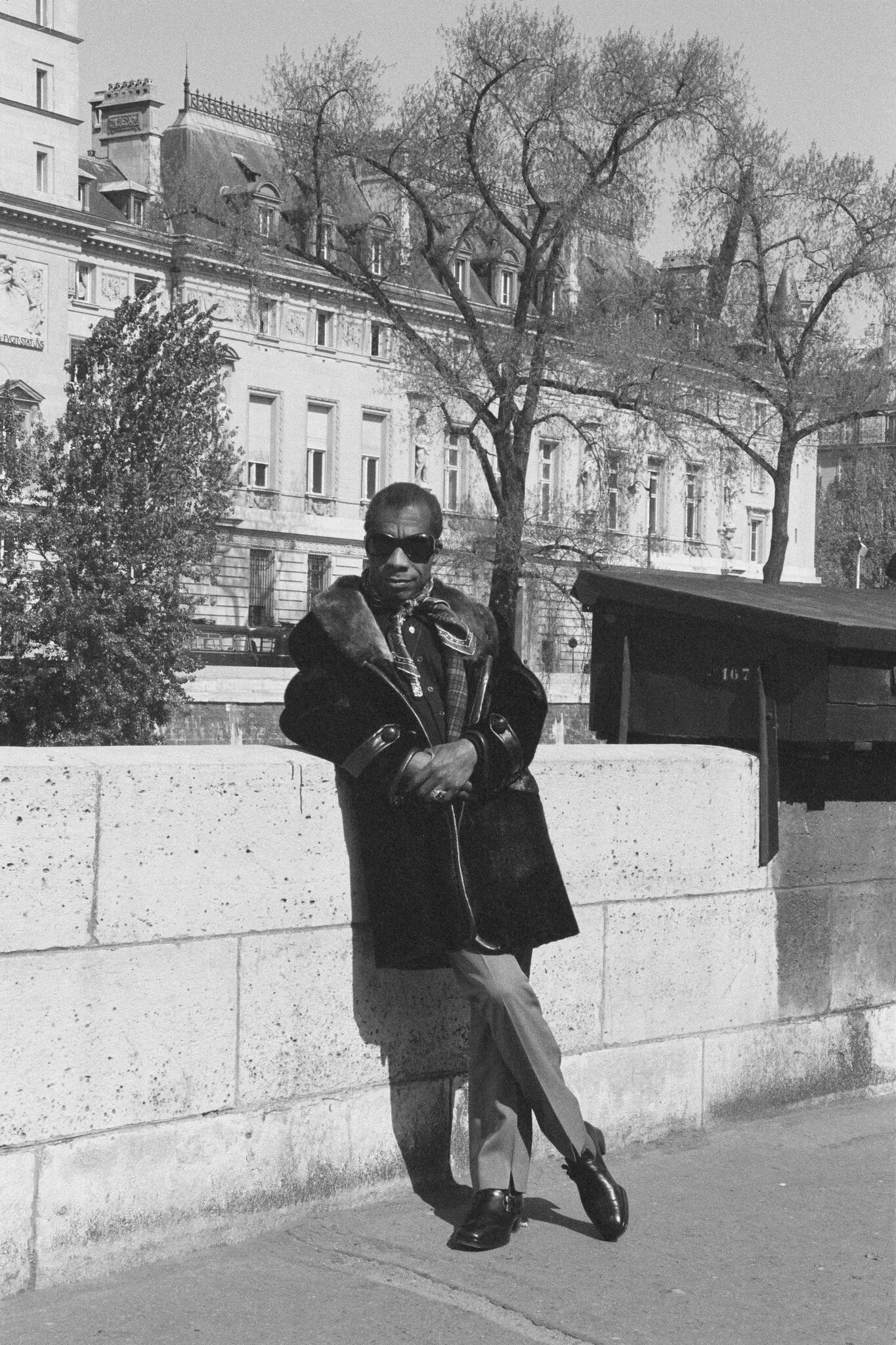

Through these archives, Johanna Makabi reveals networks of solidarity and culture: the “chosen families” formed among immigrants, the music-filled gatherings where the diaspora found joy, and the figures of the Parisian Black music scene, like Papa Wemba, captured in intimate moments. These images highlight the role of nightlife, music, and cultural spaces in shaping Black identity in Paris. They also remind us that many once-prominent figures have been forgotten, their legacies surviving only in anonymous family albums.

«We need to see ourselves outside of the framework imposed by others» Makabi emphasizes. «These archives allow us to tell our own stories, on our own terms».

The 1980s: a turning point for Black Paris

Makabi’s focus on the 1970s and 1980s is deliberate. These decades marked a shift: initially, President Mitterrand’s government introduced more open immigration policies, but later the Pasqua-Debré laws[2] cracked down on migrants. It was also the period when the children of immigrants, born and raised in France, entered the public sphere, only to be met with suspicion and hostility. «My parents were among the last generation of Africans to arrive in France with a strong belief in the country’s values and a hope for integration», Makabi notes.

Her archives offer a counter-narrative to official histories, portraying a Paris that was far more diverse than is often acknowledged.

Memory, ownership, and the fight against erasure

Preserving these archives is more than an act of remembrance: it is a form of resistance against the erasure of Black history in France. «We need these stories to piece together fragmented lives rewritten by official history», Makabi asserts. Yet, she is wary of how institutions might appropriate these narratives without truly valuing the communities they represent.

Social media has democratized access to these archives, but it has also raised questions about ownership and exploitation. «Everyone wants our stories, but no one wants to live our realities», she warns. This paradox underscores the need for autonomous Black-led spaces to safeguard and interpret these histories on their own terms.

Toward a more democratic history of Paris Noir

Reclaiming the history of Paris Noir is not just about preserving the past: it is about making that past accessible to those who lived it and their descendants. Without the voices of everyday people, we risk an incomplete and elitist understanding of Black life in Paris.

As archivists, artists, and historians continue their work, the hope is that these histories will not only be preserved but fully recognized as part of the broader public consciousness. Paris Noir is not just a relic of the past: it is a living, breathing legacy that deserves to be seen and remembered.

Notes:

[1] Dunbar, E. (1968). The Black expatriates: A study of American Negroes in exile. Praeger.

[2] The Pasqua laws (1986, 1993) and the Debré law (1997) were a series of restrictive immigration laws in France. They tightened visa requirements, made family reunification more difficult, facilitated deportations, and imposed stricter conditions for acquiring French nationality.

2. Harlem Renaissance in Paris: Art, Exile and the Paradoxes of Transatlantic Freedom

by Sandra Dibansa

One of the African-American diaspora's greatest connections with Paris was born almost 6,000 kilometres from the French capital, in the place that would become the cradle of rap music decades later. In the 1920s, Harlem was a crossroads for artists and intellectuals of African descent, driven by the first waves of the Great Migration[1]. The district became the heart of a new artistic, intellectual and political movement: the Harlem Renaissance. Spearheaded by figures such as the literary Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, this cultural effervescence called for black art that was free of racial shackles, drawing as much on pan-African values as on demands for civil rights. The movement led to the emergence of a black pride, guided by works such as Alain Locke's anthology The New Negro (1925).

As the First World War drew to a close, the first Afro-Americans to settle in Paris spread the movement across the Atlantic. Around this time, the presence of black soldiers in the American army during the Great War - notably the 369th Infantry Regiment, nicknamed the Hellfighters and led by James Reese Europe - introduced jazz to French soil. This first contact had a lasting impact on the Parisian cultural scene and paved the way for an artistic migration that intensified between the wars. Richard Wright, Lois Mailou Jones as well as Claude McKay moved to Montmartre and Saint-Germain-des-Prés, attracted by the promise of artistic recognition unattainable in the United States. In Paris, Afro-American intellectuals rubbed shoulders with those from the Caribbean and African diasporas. Their converging ideals provided fertile ground for movements such as Négritude.

Fleeing a White America…

A setting conducive to the emancipation of African-Americans in search of freedom, Paris quickly became an extension of the Harlem renaissance. According to historian Tyler Stovall in his book Paris noir: African Americans in the City of light (1996), the French capital represented a place where the absence of segregationist laws, as well as the fascination with art from African and Afro-diasporic cultures, enabled Black Americans to be seen above all for their arts. James Weldon Johnson, a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance, explains that they were treated as Americans before being treated as Blacks. In his autobiography Along This Way (1933), the writer stressed that his American nationality contributed greatly to his appreciation of the city: «One thing which greatly contributed to my enjoyment was the fact that I was an American. Americans are immensely popular in Paris».

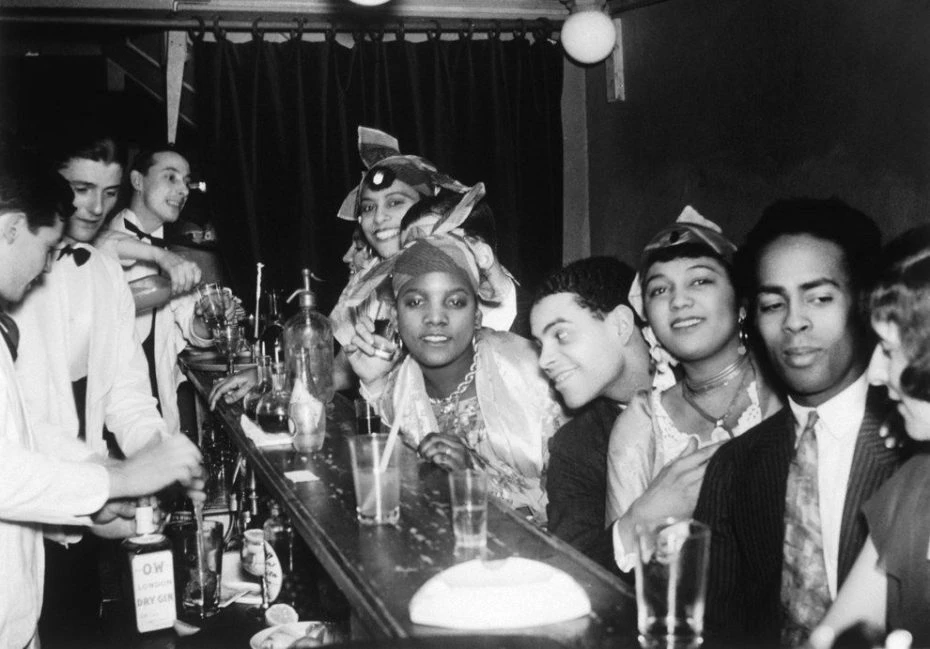

With this French enthusiasm for others, jazz became the language of a changing modernity in the cabarets of Montmartre. The iconic charleston dancer Ada Smith - nicknamed “Bricktop” for her red hair - is a good illustration of this phenomenon. Formerly manager of the Grand Duc, where she befriended Langston Hughes, she opened her own cabaret, Chez Bricktop, in the Pigalle district in 1926. There she welcomed the artists and intellectuals of the time. Her impact helped to make black American music the basis of a new cultural scene in Paris. The City of Lights was also a gentler place for the virtuoso Sidney Bechet, who found an audience there that gave him a legitimacy that would take time to achieve in the United States.

...Embracing a Drab Paris

But beware - the idea of a colourblind France is just an illusion. The Parisian avant-garde's infatuation with Afro-descendant forms of expression was brimming with exoticization. In works such as Paul Colin's Le Tumulte Noir (1927), which sublimates the energy of black cabarets while enclosing them in “savage” imagery, Afro-American culture was staged according to codes inherited from the French colonial imagination.

This imagery also extends to black female artists, who are often confined to hypersexualised roles. The concept of the Black Venus, analysed by T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting in Black Venus: Sexualized Savages, Primal Fears, and Primitive Narratives in French (1999), illustrates how the performances of Afro-descendant women are perceived through an ambiguous fascination. While Josephine Baker's success was partly based on her acceptance of these codes, other artists sought to break free of them. Like Bricktop, who imposed a more sober style, refusing to take on the fantasised role of the exotic dancer.

Researcher Brent Hayes Edwards sums up this tension in The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism (2003). In this work, he explores the way in which black art became avant-garde entertainment for the Parisian elite while remaining locked within a white gaze. Paris, far from being a genuine space of freedom, constantly compelled Afro-American artists to navigate between recognition and fetishisation.

(Re)birth of a Black Consciousness

Like the one that began in Florence in the 14th century, the Harlem Renaissance was characterised by the enhancement of ancient cultural heritages. By way of background, the signing of the Treaty of Versailles enabled the French colonial empire of the interwar period to reach its apogee. Many artefacts were looted and then exhibited in Paris museums. These works inspired artists such as Pablo Picasso, who took a Cubist turn when he saw African masks. There was no shortage of African-American artists living in Paris. Their exposure to African art had a profound effect on their work, prompting them to reclaim an aesthetic and cultural connection that had been interrupted by slavery.

Arriving in Paris in 1937, Loïs Mailou Jones first painted scenes of Parisian life before signing one of her best-known paintings, Les Fétiches, in 1938. Inspired by the artefacts the artist discovered in France, the modernist-style canvas reveals five floating masks against a black background. In Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America (1994), the painter and writer David Driskell points out that this encounter with African art in colonial territory gave African-American artists a new awareness of their own diasporic heritage. However, the interest in these objects presented through a white lens questions the way in which Harlem Renaissance artists were able to address a purloined legacy of African culture.

This reflection on black identity went beyond the simple circle of the Harlem Renaissance. In Paris, African and Caribbean thinkers found in the movement a source of inspiration for formulating their own cultural and political demands. The Martinique-born Aimé Césaire, his Guyanese friend Léon-Gontran Damas and the future Senegalese president Léopold Sédar Senghor frequented Paulette Nardal's literary salon, where they debated with their African-American namesakes. Here they became familiar with novelists and poets Claude McKay and Langston Hughes. Out of these discussions came in 1931 - at the instigation of the Nardal sisters - La Revue du Monde Noir, a bilingual art and literature publication dealing with both anti-colonialism and black consciousness. The periodical captured the intellectual effervescence of the time and sketched the climate in which the literary and political current of Négritude emerged.

A Fleeting Movement?

The Harlem Renaissance faded away at the end of the 1920s with the stock market crash and the Great Depression that followed. Despite this abrupt halt, it was difficult to imagine any lasting continuity for this Afro-American revival in France. Despite the atmosphere of relative freedom that characterised Paris in the eyes of black American artists, their presence was still marked by a form of cultural assignment. Richard Wright, an African-American man of letters who became a naturalised French citizen in 1947, explained in an interview that in France it was easier for blacks to exist «in places of entertainment, distraction [...] because we want to laugh with blacks, but we don't want to work with blacks.» (Entretiens avec Richard Wright 4/8 : entre deux mondes, by Georges Charbonnier for France III Nationale, 1960). The French capital only allowed them to be free within a restricted framework.

Paris failed to develop a truly rooted African-American community. Unlike Harlem, the City of the Enlightenment remained a stopping-off point for many of the artists of the Harlem Renaissance. In his autobiography, A Long Way from Home (1937), Claude McKay wrote that «the cream of Harlem was in Paris», but he made no secret of the fact that he did not feel attracted to the city. Distraught by his condition, the journalist Louise Bryant went so far as to tell him one drunken night: «Go home to Harlem or back to Africa, but leave Paris». History was enough to stifle the movement in the French capital, as the Second World War marked the end of the influence of jazz - deemed corrupt by Nazi Germany. African-Americans left an invaded Paris for the United States, which was simmering at the dawn of the American Civil Rights movement.

Although it took place over a short period, the Paris branch of the Harlem Renaissance left a lasting mark on the artistic and intellectual productions of the African and Afro-diasporic communities.

Notes:

[1] The rural exodus of black Americans who had left the South and the Jim Crow laws to settle in the cities of the North

3. “Peace Love Unity and Having Fun”: how hip hop brought New York to Paris

by Mona Koyamba

In New York City, in the South Bronx district of the 1970s, plagued by racism and segregation, a block-street party was organized, the Campbell siblings[1], held on 11 August 1973. This date marked the birth of hip hop culture, bringing together DJing (music mixing), rap, breaking and graffiti, promoting the values of sharing and challenge. It settled in France in the mid-1980s, through the ‘New York City Rap Tour’, organised by journalist and music producer Bernard Zekri, gathering pioneers of the movement like Futura 2000, the Rocksteady, or the Double Dutch Girls in Paris. Then, came the TV programme H.I.P H.O.P, the first to showcase hip-hop culture with the first Afro-French TV host, Sidney Duteil. More than entertaining, H.I.P H.O.P was a «conservatory»[2], allowing the new hip hop lovers, and especially Afro descent, to build their own identity upon an unprecedented culture, «given that there [were] no guardian figures representing [French] African men and women on screen, in the end [they were] obliged to build ourselves on black American culture»[3].

In this context of cultural importation, dance and fashion became one of the most visible aspects of this culture, appearing in music videos and TV shows through different styles and recognizable outfits, gaining more and more attention across France and its capital, Paris. In this city, this movement turned into a mainstream and intercultural phenomenon, inspiring the French Afro-descent who saw this way of moving and styling as an opportunity to express themselves and to connect with people who share similar life experiences.

Hip-hop as a way of moving and connecting people above the borders

At its arrival in Paris, the French audience was seduced by the different dances that accompany this movement, starting with breaking. The people of the suburbs in quest of identity, saw in the aerial combination of “top rocks” (steps) and “tracks” (figures on the ground), the freedom they were looking for, «projec[ting] [themselves] into the future through this dance»[4]. Alongside breaking, there is a panel of “stand-up styles” coming from the streets or the clubs: hype, locking, hip hop (or hip hop freestyle), smurf, popping, krump, waacking, voguing, house and the list can continue. All these styles were developed in the US, before France made them their own. Inspired by the movements in the music videos, in the improvised classes given in Châtelet, or in the cyphers in front of the Eiffel Tower, talented French dancers began to emerge. In the early 2000s, Afro descent dancers like Meech de France[5], Yugson, and ICEE met and challenged the African American to their own game, sometimes winning, sometimes losing, but always enriching the culture and gaining precious knowledge that would be transmitted to other dancers back in France.

Professional traineeships were established in the early 2000s, to teach the basics of the different dance styles, like the Juste Debout School or the Flow Dance Academy. A hip hop section was created in the Turgot high-school, in the 3rd district of Paris. A first in France, where this kind of section usually concerns sports such as football or basketball. Challenge being at the heart of the hip hop dances, Paris also became one of the main places for peer recognition, with events that have become rites of passage for upcoming hip hop dancers. One of these not-to-be-missed experiences is the “Juste Debout”, imagined by the popper Bruce Ykanji with a first edition held in 2002. Gaining in popularity throughout the years, this event turned into an emblem of the Parisian cultural landscape, reuniting dancers from all styles and countries in the biggest concerts halls[6].

France began to emancipate from their American pioneers, incorporating other influences (martials arts, ballet, contemporary dance, etc.) in their dances. Hip hop dances went from being performed in the streets (or clubs) to being performed on stage by dance companies, like the company Black Blanc Beur, founded by Jean Djemad and Christine Coudun in 1984; or the company Käfig, created by Merwan Merzouki in 2003; or even the company Carmel Loanga, which emerged in the late 2010s. Festivals have started to be held all over France, like the festival Kalypso in Paris, organized by Merwan Merzouki, which offers the companies the opportunity to perform unique and hybrid pieces in front of a selected jury. A new step has been taken with the breaking being present at Paris Olympic Games in 2024, attesting the role of the city in the worldwide cultural impact of hip hop culture.

However, this institutionalization of hip hop dances is controversial, especially concerning a potential “de-naturalization” of the culture, which was, at the beginning, unacademic[7]. This debate can also be explained by the fact that hip hop being an oral culture, its interpretation can differ and key information can be lost in translation. That is why some structures (museums, dance studios, associations) tried to sustain a dialogue between France and the US through expositions like “Hip Hop 360”[8], and by inviting pioneers of the culture like Buddha Stretch in workshops. The aim was to retrace the roots of hip-hop culture so as not to lose the memory of the journey that brought us here.

A fashion without borders

More than a way of moving, hip hop is also a way of styling, an “extension of the art”[9] migrating from the ghettos to the runaways, and from New York to Paris. The sneakers, the baggy, the hoodie, the big jewelry, the cap. All these recognizable pieces of clothing accompany the corporal movement of the graffer, the DJ, the rapper, the dancers, building a distinctive and identifiable image that makes us say “this is hip hop”.

It started on a local level, with pioneering designers like Dapper Dan, who opened in 1982 the first hip hop shop in Harlem. This store showcased what became known as “logo mania”, a fashion trend that combined large logo versions of high fashion brands such as Gucci or Louis Vuitton with streetwear design from hip hop culture. At the same time, the well-known rap group Run Dmc signed a partnership with Adidas. Their commercial song My Adidas, embodied the streetwear trend by making the jogging and the Adidas Superstar their trademarks. Hip hop fashion was thus plural, oscillating between the amplitude of streetwear and the colourful influences of West Africa[10], with Kente fabric caps, flashy trousers and extra large jewelries.

This new way of clothing was being recognized by the fashion industry, also thanks to the emerging hip hop brands like FUBU, founded in 1992 by Daymond John, or Rocawear, created by Jay Z and Damon Dash in 1999. Worn by African American rappers and dancers in video clips and commercials[11], these brands progressively gain more visibility, grossing large amounts of money and anchoring their legacy in the industry. In the late 1980s, these new brands and outfits were exported to the French capital of fashion, attracting the people of the suburbs, who made these new designs their own. Soon, we began to see baggys, caps, bobs, bombers, leather jacket, necklaces, joggings and sweets on the TV Show H.I.P H.O.P, as well as in videos clips of French rap crews like: NTM, Funky Family, Arsenik, or the Ladie’s Night, one of the rare female rap and double dutch crew[12].

The clothes were not only stylish pieces of fabric. They also had a social function: wearing the same kind of clothes created a sense of community, embodying the famous motto of the Zulu nation «Peace Love Unity and Having fun»[13]. The best example was the “Ticaret boutique”, located in the 10th district of Paris. Founded in 1986 by Daniel, a French Afro-descent and hip hop lover, it was first meant to be a random thrift shop, but its location near the wasteland of La Chapelle - one of the places where hip hop started in France according to the hip hop activist Ambre Foulquier[14] - changed everything. Daniel started to import clothes from New York: bombers, baseball jackets, baggys, caps, etc. He tried to meet the demands of his growing customer base by unearthing never before-seen pieces. What was a random thrift shop, turned into a multidisciplinary hip hop temple, welcoming wardrobes, but also mixtapes from emerging rappers like Clyde from the crew Assassin[15]. Before closing in 1998, the Ticaret store had gathered different generations of the hip hop movement around clothes, building its long lasting legend and a bridge between the African descent communities above the Atlantic.

In the 21st century, as hip hop managed to settle durably in the fashion industry, with designers like Sergio Hudson or Virgil Abloh, the fashion dialogue between France and the US has intensified.

Firstly, through collaborations with French luxury brands. Succeeding the late Virgil Abloh, Pharrell Williams entered this institution as the new designer for the men's collection. This unprecedented arrival allowed an African American, a man of hip hop and a fashion lover, to challenge the elegance “à la française”, by shedding light on a culture that has long been stigmatised and discriminated against for being too ghetto, too black. His 2024 Men Spring-Summer Collection made hip hop taking the center stage of the Parisian fashion world, with a streetwear runaway putting on the foreground the “traces of hip hop golden age”[16].

Secondly, through the multiplication of hip hop stores like Ticaret: Ekirock, Scred Boutique, HollyHood Capital, Flipside, and Isakin, to name a few.

And last but not least, through the re-appropriation of hip hop fashion by Afro descent hip-hop ambassadors. From Sexion d’Assaut to Tiakola, from the Ladie’s Night to Shay and Aya Nakamura, and so on, French Afro descent artists from Paris have redefined the codes of hip hop fashion, adapting them to their reality and influences, with a combination of classic, vintage and modernity.

Through its dances and fashion, hip hop never stopped to connect the French Afro descent communities with their American neighbors, instigating a constant dialogue and a mutual influence that will keep reshaping and evolving in the future, resulting in new designs and hybrid genres.

Notes:

[1] Cindy and Clive, aka DJ Kool Herc

[2] Quote of the choreograph Merouad Merzouki in the documentary « #1 : Premier pas - La culture hip-hop en Île-de-France : 40 ans d’ébullition artistique - YouTube ». Consulted on February 22, 2025 février 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0ik6LPCKI8&feature=youtu.be

[3] Quote of the french rapper KoHndo in the documentary « #1 : Premier pas - La culture hip-hop en Île-de-France : 40 ans d’ébullition artistique - YouTube ». Consulted on February 22, 2025 février 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0ik6LPCKI8&feature=youtu.be

[4] Quote of the choreograph Merouad Merzouki in the documentary « #1 : Premier pas - La culture hip-hop en Île-de-France : 40 ans d’ébullition artistique - YouTube ». Consulted on February 22, 2025 février 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0ik6LPCKI8&feature=youtu.be

[5] Benbekaï, Yasmina. « Meech : “La House Dance fait partie de la danse Hip Hop” ». Mouv’, January 22, 2020. https://www.radiofrance.fr/mouv/meech-la-house-dance-fait-partie-de-la-danse-hip-hop-7156120.

[6] The next edition of the Juste Debout was held at the Accord Hotel Arena, one of Paris biggest concert hall, on 2nd March 2025

[7] Hip-hop : pourquoi la loi 1149 pose problème ?, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lUo-nWBHPHA.

[8] An exhibition on the history of hip hop and its arrival in France, organised by the Philharmonie de Paris in 2022.

[9] 50 Years of Hip Hop & High Fashion: The Evolution from Streetwear to Runways, 2023.

[10] La mode hip-hop s’expose sous toutes les coutures, 2025. https://www.lemonde.fr/decodages/article/2015/05/13/la-mode-hip-hop-sous-toutes-les-coutures_4632998_4606750.html.

[11] In 1999, the rapper LL Cool J gave a freestyle for a Gap commercial while wearing a FUBU cap

[12] Du Double Dutch aux Ladie's Night : Pascale Obolo, pionnière du hip-hop en France | INA HIP-HOP, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5EDcsmiJ-4g

[13] Les codes vestimentaires du hip-hop en 1990 | INA HIP-HOP, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XHphNvGs6V0.

[14] 1996 : visite de la boutique Ticaret, l’antre du hip-hop 👟 | INA HIP-HOP, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-knxM5NLfTQ.

[16] The cultural journalist Soumya Krishnamurthy in the documentary 50 ans du hip-hop : de Pharrell à Dapper Dan, comment le hip-hop a bouleversé la mode (épisode 3), 2023.

References

Bibliography

1. The people’s Paris Noir: everyday lives, unarchived

Dunbar, E. (1986). The black expatriates: a study of American Negroes in exile. New York: Dutton.

2. Harlem Renaissance in Paris: Art, Exile and the Paradoxes of Transatlantic Freedom

Colin, P. (1927). Le Tumulte Noir. Paris, France: Éditions d'Art.

Driskell, D. (1994). Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America. New York, NY: Abrams.

Edwards, B. H. (2003). The Practice of Diaspora: Literature, Translation, and the Rise of Black Internationalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fabre, M. (1991). From Harlem to Paris: Black American Writers in France, 1840-1980. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Gates, H. L. (1988). The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, J. W. (1933). Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson. New York, NY: Viking Press.

Locke, A. (1925). The New Negro: An Interpretation. New York, NY: Albert and Charles Boni.

Sharpley-Whiting, T. D. (1999). Black Venus: Sexualized Savages, Primal Fears, and Primitive Narratives in French. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Stovall, T. (1996). Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Articles

1. The people’s Paris Noir: everyday lives, unarchived

1986 : La première loi Pasqua. Hommes et Migrations, n°1095, septembre 1986, n°1096, octobre 1986, n°1118, janvier 1989. https://www.histoire-immigration.fr/les-50-ans-de-la-revue-hommes-migrations/1986-la-premiere-loi-pasqua

2. Harlem Renaissance in Paris: Art, Exile and the Paradoxes of Transatlantic Freedom

Encyclopædia Britannica. (n.d.). Great Migration. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Migration

Encyclopædia Britannica. (n.d.). Harlem Renaissance. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/Harlem-Renaissance-American-literature-and-art

Libération. (2019, February 26). Paulette Nardal, théoricienne oubliée de la Négritude. Libération. Retrieved from https://www.liberation.fr/debats/2019/02/26/paulette-nardal-theoricienne-oubliee-de-la-negritude_1711727/

OpenEdition Journals. (2021, October 6). De la survisibilité/invisibilité sociale à la colère politique. Tracés: Revue de sciences humaines, 35. Retrieved from https://journals.openedition.org/teth/5873

OpenEdition Journals. (2020, February 7). Le rôle des avant-gardes et de l’exotisation. Études africaines, 68(2). Retrieved from https://journals.openedition.org/etudesafricaines/14952

Palais de la Porte Dorée. (n.d.). Le contexte colonial français en 1931.

Palais de la Porte Dorée. Retrieved from https://monument.palais-portedoree.fr/le-contexte-colonial/l-empire-colonial-francais-en-1931

Radio France Internationale (RFI). (2023, April 8). "Le cubisme est né en Afrique": Entre Pablo Picasso et l'art africain, une histoire d'inspiration. RFI. Retrieved from https://www.rfi.fr/fr/culture/20230408-le-cubisme-est-n%C3%A9-en-afrique-entre-pablo-picasso-et-l-art-africain-une-histoire-d-inspiration

Radio France Internationale (RFI). (2024, June 8). Brent Hayes Edwards et sa pratique de la diaspora noire. RFI. Retrieved from https://www.rfi.fr/fr/podcasts/en-sol-majeur/20240608-brent-hayes-edwards-et-sa-pratique-de-la-diaspora-noire

Universalis.fr. (n.d.). Sidney Bechet et le jazz en France. Universalis. Retrieved from https://www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/what-is-this-thing-called-love-bechet-sidney/

3. “Peace Love Unity and Having Fun”: how hip hop brought New York to Paris

Générations. (2025, February 22). Ticaret ou l’histoire du tout premier lieu parisien dédié au Hip-Hop. Générations. Retrieved from https://generations.fr/news/culture-et-societe/61894/ticaret-ou-l-histoire-du-tout-premier-lieu-parisien-dedie-au-hip-hop

INA. (2025, February 22). Le hip hop, une danse migratoire. Danses Sans Visa. Retrieved from http://fresques.ina.fr/danses-sans-visa/parcours/0003/le-hip-hop-une-danse-migratoire.html

Le Monde. (2015, May 13). La mode hip-hop s’expose sous toutes les coutures. Le Monde. Retrieved from https://www.lemonde.fr/decodages/article/2015/05/13/la-mode-hip-hop-sous-toutes-les-coutures_4632998_4606750.html

Movies and Videos

1. The people’s Paris Noir: everyday lives, unarchived

Makabi, J. (Director). (2021). Paulette et le Clown

Makabi, J (Director). (2022). Notre mémoire

3. “Peace Love Unity and Having Fun”: how hip hop brought New York to Paris

50 ans du hip-hop. (2023). De Pharrell à Dapper Dan, comment le hip-hop a bouleversé la mode (épisode 3) [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mEKTX2wyK_c

50 Years of Hip Hop & High Fashion. (2023). The Evolution from Streetwear to Runways [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZF6mOlqF0U

Hip-hop. (2024). Pourquoi la loi 1149 pose problème ? [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lUo-nWBHPHA

INA HIP-HOP. (2025). 1996 : visite de la boutique Ticaret, l’antre du hip-hop 👟 [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-knxM5NLfTQ

ORIGinaL #ina. (2025, February 22). Du Double Dutch aux Ladie’s Night : Pascale Obolo, pionnière du hip-hop en France [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5EDcsmiJ-4g

Premier pas. (2025, February 22). La culture hip-hop en Île-de-France : 40 ans d’ébullition artistique [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0ik6LPCKI8&feature=youtu.be

Music/Podcast

2. Harlem Renaissance in Paris: Art, Exile and the Paradoxes of Transatlantic Freedom

France Culture : Richard Wright : Quand j’écris, je ne suis pas conscient que c’est une idée blanche ou une idée noire. https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/les-nuits-de-france-culture/richard-wright-quand-j-ecris-je-ne-suis-pas-conscient-que-c-est-une-idee-blanche-ou-une-idee-noire-8152364

3. “Peace Love Unity and Having Fun”: how hip hop brought New York to Paris

#105. Culture. Fondamentaux HIP HOP. par TOUS DANSEURS ». Consulted on February 22, 2025 février 2025. https://creators.spotify.com/pod/show/tousdanseurs/episodes/105--Culture--Fondamentaux-HIP-HOP-e1dfj72.

Benbekaï, Yasmina. « Meech : “La House Dance fait partie de la danse Hip Hop” ». Mouv’, January 22, 2020. https://www.radiofrance.fr/mouv/meech-la-house-dance-fait-partie-de-la-danse-hip-hop-7156120.

Fresh Fly Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop Style, an interview with Elena Romero and Elizabeth Way, part 1, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/episode/1YvR1kaNOmEC4557DdTx54.

Fresh Fly Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop Style, an interview with Elena Romero and Elizabeth Way, part 2, 2023. https://open.spotify.com/episode/502qGecIhx7D0JPmvYY1xI.

Websites

3. “Peace Love Unity and Having Fun”: how hip hop brought New York to Paris

« Hip-Hop 360 | Philharmonie de Paris ». Consulted on February 22, 2025 février 2025. https://philharmoniedeparis.fr/fr/activite/exposition/23375-hip-hop-360.

Donate

Donate